A program run out of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency that seeks to prioritize critical infrastructure companies does not do enough to include cybersecurity concerns, according to an audit by the Governmental Accountability Office.

CISA is perhaps best known for its work around cybersecurity, but the agency’s writ also includes helping to protect infrastructure from physical threats. The GAO was tasked by Congress with studying the assistance CISA provides to critical infrastructure entities and how that work is prioritized.

The agency’s National Critical Infrastructure Prioritization Plan helps identify systems and assets that could have “national or regional catastrophic effects” if destroyed or disrupted. The agency also stood up a National Risk Management Center that developed a list of more than 100 “critical” national functions – from internet and telecommunications to elections and the food supply – that could have cascading negative effects across multiple parts of society if disrupted.

That list too was supposed to feed into the agency’s ongoing cybersecurity assistance programs, which include webinars, training, tabletop exercises and technical tools and assessments, but partners both inside and outside the government told auditors that they rarely use it and don’t understand how it fits in with other workstreams.

“Although CISA initiated the [critical] functions framework in 2019, most of the federal and nonfederal critical infrastructure stakeholders that GAO interviewed reported being generally uninvolved with, unaware of, or not understanding the goals of the framework. Specifically, stakeholders did not understand how the framework related to prioritizing infrastructure, how it affected planning and operations, or where their particular organizations fell within it."

Interviews with 12 CISA officials and stakeholders in the water and wastewater, energy, critical manufacturing and information technology sectors found that the NCIPP list was out of step with the current threat environment. For the highest priority designation, the impact of their destruction or disruption must meet minimum thresholds for consequences, including economic loss, fatalities, degradation of national security and mass evacuation length. It also focuses on attacks that take down multiple assets in a short period of time.

But agency officials say today the greatest threats facing critical infrastructure are from cyber attacks, and extreme weather. In fact, weather and climate related events did more than $91 billion of damage across the U.S. in 2018 alone. Further, the past year has shown that successful attacks against single entities (like Colonial Pipeline) are more than capable of causing widespread service or supply disruption if they are hit with ransomware or other a cyber attack.

Critical infrastructure owners and operators who were interviewed reported that the data was often not “accurate, relevant, consistent or reflective of infrastructure risk,” a criticism that multiple agency officials agreed during interviews, while feds from designated Sector Risk Management Agencies often had copies of the list but generally did not use them

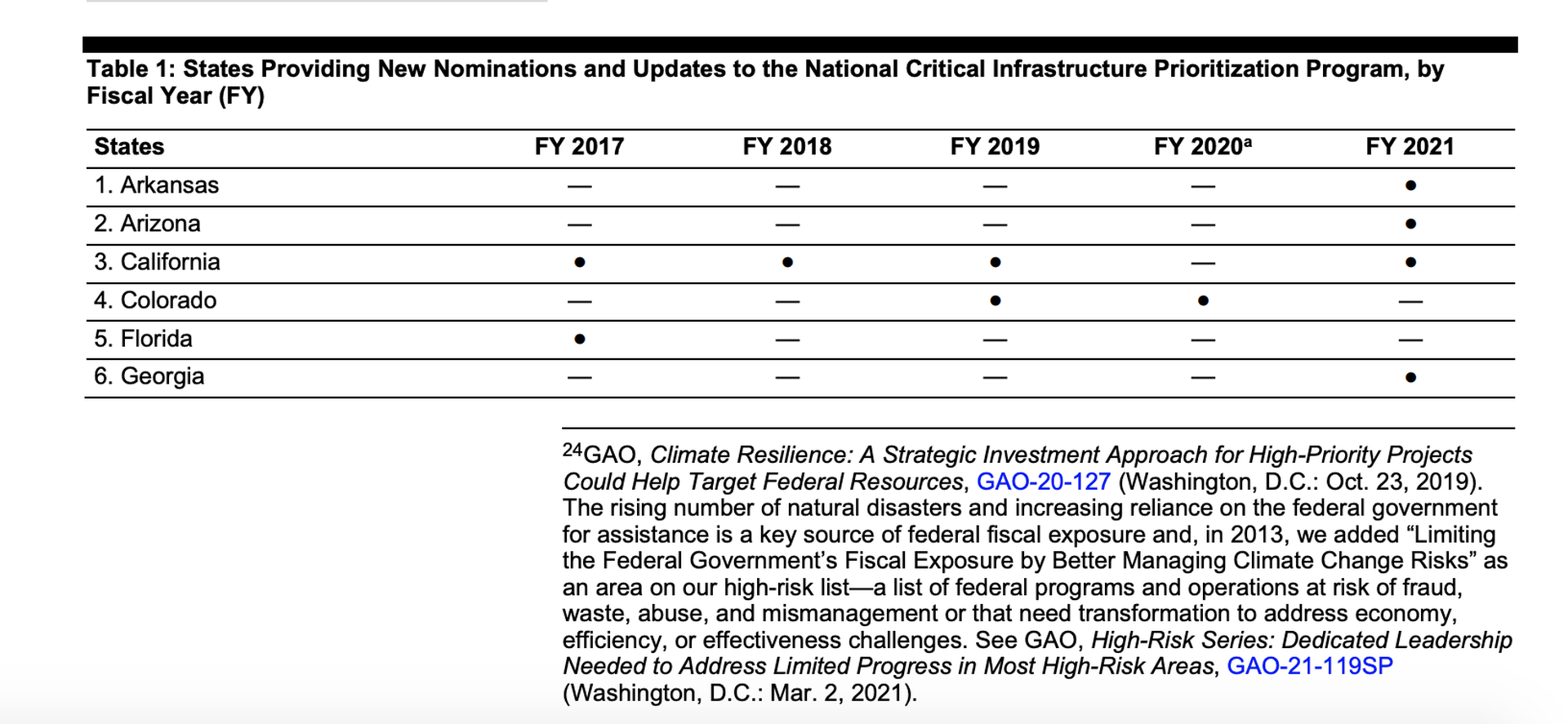

It doesn’t appear that states are making much use of the NCIPP either: just 14 states have nominated assets for inclusion on the list or requested updates between 2017 and 2021. Between 2018 and 2021, the agency added just 38 assets to the list – including just five priority 1 assets – and rejected hundreds of others that were nominated for inclusion. CISA attributed the low numbers in part to statutory restrictions.

It also details problems that CISA headquarters has had coordinating its cybersecurity assistance with its 10 regional branch offices since they were stood up as an operational component agency in 2018.

“According to regional staff, their ability to effectively coordinate the cybersecurity services that CISA headquarters delivered was impaired because of staff placement following the reorganization. Specifically, staff conducting outreach and offering a suite of cybersecurity assessments to critical infrastructure stakeholders are located in regional offices, while CISA offers additional cyber assessment services using staff from a different division—the Cybersecurity Division—which operates out of headquarters,” GAO auditors wrote.

One area where infrastructure owners praised the agency was around its information sharing, sending proactive alerts and advisories on a range of cyber threats and campaigns both specific and general, and that such advice generally included concrete, actionable steps for defenders to take in response.

Auditors made six recommendations for the agency, including updating CISA’s process for prioritizing critical infrastructure to include current threats in cyberspace, getting input from states that aren’t using the NCIPP list or nominating assets, ensuring other stakeholders are involved, improving communication between headquarters and regional offices and developing regional-specific threat intelligence products.

In a response attached to the audit, department liaison Jim Crumpacker said the agency agreed with the recommendations and said CISA Director Jen Easterly issued a memo in January 2022 updating its communication and coordinating policies with regional offices, while a formal process for ingesting feedback from regional offices was stood up in February.