Information security has rarely been considered sexy. That’s probably still the case today, but a series of damaging hacks to federal agencies and an onslaught of crippling ransomware attacks on industry over the past year have grabbed the attention of decisionmakers in the corporate boardroom and the halls of Congress alike.

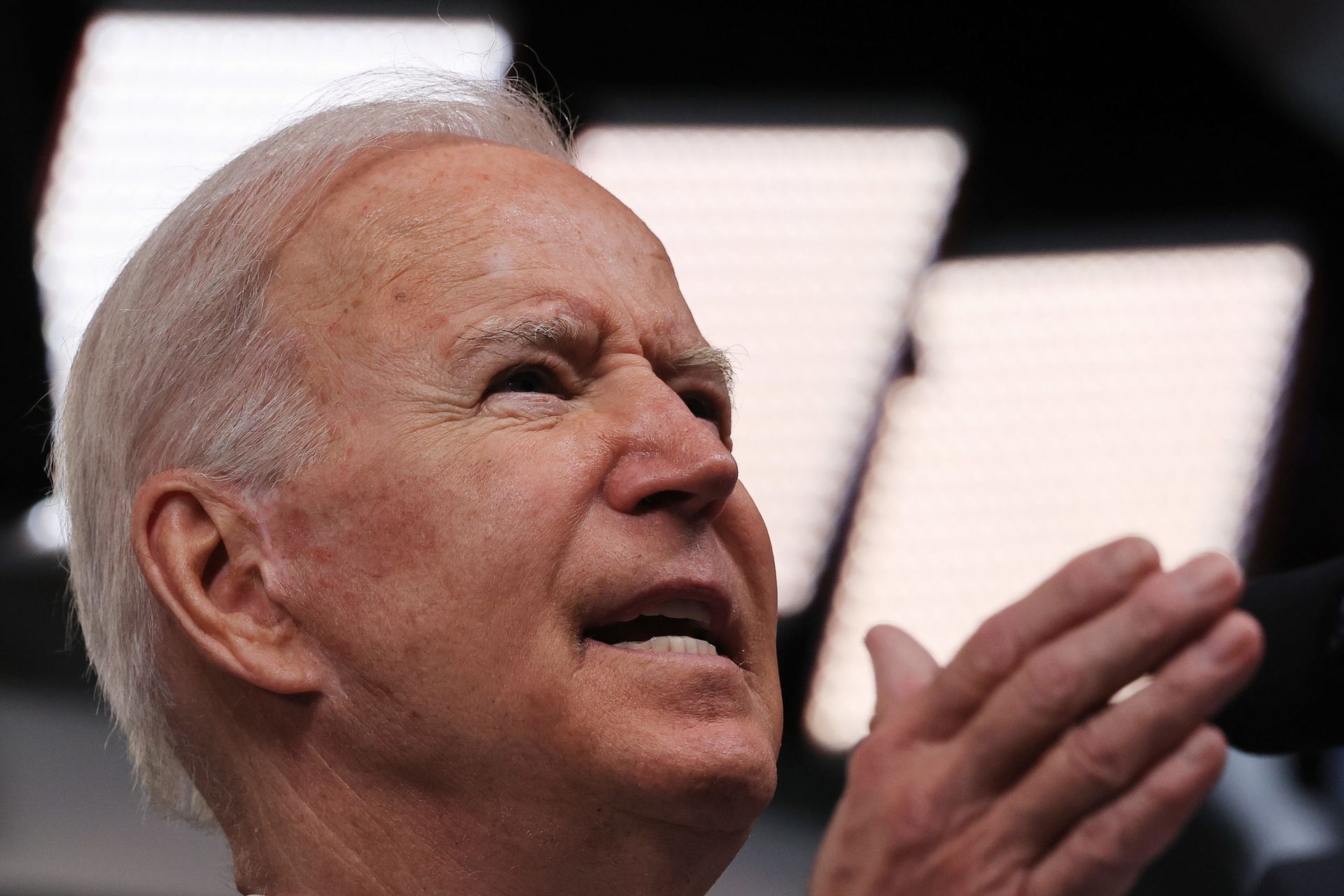

Those incidents set the stage for what many believe has been the most active year ever in cybersecurity policy, as the Biden administration has executed a bevy of orders, directives, reorganizations, programs, summits, offensive cyber operations and other initiatives that has impacted virtually every sector, industry and technology consumer in the country.

Incidents like the SolarWinds campaign and the Colonial and JBS ransomware attacks are often categorized in Washington as “wake-up calls” or presented as singular, discrete and catastrophic events. It is probably more accurate to look at these incidents as the straws that finally broke the camel’s back, building off years of similar activity in the past that were largely met with indifference or lip service by industry titans and government largely uninterested in making changes to the status quo.

Today, tech companies and critical infrastructure entities are working more closely with the federal government than they ever have before. Often this collaboration is still done voluntarily, out of a mutual understanding of how the public and private sector’s fates are intertwined. However, policymakers are now increasingly open to legislation or regulations that force businesses to improve their security posture and report cyber incidents when they intersect with the public’s interest.

On the government side, agencies have been given hard mandates to implement baseline protections, like multifactor authentication and encryption, that have been considered industry best practices for decades but failed to break through the internal bureaucracy within the federal government. They’re also being pushed to implement newer ideas, like zero trust architecture and endpoint detection and response (EDR) systems, that could set the stage for more advanced methods of cyber defense down the line.

At the head of it all is a White House that has approached policymaking over the past nine months as if it is more concerned about the cascading, cross-sectoral impacts of a major cyber incident than ruffling industry feathers around regulation.

Eric Mill, a senior cybersecurity advisor to the White House at the Office of Management and Budget, said a number of “large scale” attacks over the past year have prompted the White House to take more aggressive action. Initiatives like the zero trust push in government were in part an effort to play catchup on basic cyber hygiene practices as well as taken advantage of newer technological developments.

“The things that we’re doing, I would say, are a mix of things that are new and old. There are bread and butter cybersecurity things, like encryption and multifactor authentication, things we’ve known about for a while and it’s time to really bear down now,” said Mills earlier this month. “And then there are things that are newer that have matured over the last several years … policy approaches or alternatives to VPNs or even when it comes to multifactor encryption, newer approaches to doing those things that make them easier to deploy at scale and automate operations around them.”

An uncertain record in a brave new world

Many observers argued that, judged on pure volume alone, the first year of the Biden administration has been more active on cybersecurity policy than virtually all other presidential administrations in total.

“I think it’s got a level of presidential attention that is unprecedented, clearly,” Suzanne Spaulding, who led what is now the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, told SC Media.

Spaulding pointed to both substantive developments — such as imposing real regulatory requirements on industry and installing respected experts like Anne Neuberger and Chris Inglis to top White House roles — as well as rhetorical and aesthetic choices, like hosting high-profile summits with businesses on cybersecurity, international partners on ransomware and even mentioning cybersecurity multiple times in his first joint address to Congress.

In the past, these issues were often considered too niche to warrant high-profile public relations efforts. In a world where gas prices and food supply are affected by cyberattacks, the Biden White House and other policymakers are keen to show that they’re taking the issue seriously.

In some areas, this White House is riding waves that have been built up in past administrations. Lawmakers like Sen. Gary Peters, D-Mich., have said that “ransomware has changed the equation” when it comes to the willingness of Congress and government to consider new regulations on the private sector.

Hacks like the SolarWinds incident also led the government to realize “how interconnected security is” between government and contractors and how “a breach of their security is a breach of yours,” former Deputy Assistant Attorney General Kellen Dwyer told SC Media earlier this month.

Others are less impressed with the administration’s record. Edgard Capdevielle, CEO of Nozomi Networks, a firm focused on IT and OT security in critical infrastructure, said that despite the flurry of activity and initiatives since January, the U.S. by and large remains far too willing to tolerate threats like ransomware and set policy based on whatever latest incident hits the news.

The claim that Biden has run the most active cybersecurity policy shop ever is “factually correct, but it’s ridiculously insufficient,” he told SC Media.

“You have two [approaches]: one is being really visionary, proactive, and the other is inertia,” said Capdevielle. “I think this is extremely reactive and inertia-based, 100 percent.”

He argued many of the administration’s changes, like mandating multifactor authentication for government employees and contractors or increasing reporting requirements on the private sector — seem aggressive or substantial only when compared to the negligence and inaction by past administrations. When measured against the scope of the actual threats faced from government hacking groups and ransomware campaigns, it still falls woefully short.

“What we’re talking about today, whether we’re talking about SolarWinds, whether we’re talking about Colonial Pipeline, is the beginning of something huge and we’re not doing nearly enough,” said Capdevielle. “Our government is very reactive and moves at government speed.”

Threads of continuity

While the Biden White House has moved more aggressively in this space than any other president, in some respects their prescriptions have built on top of foundations laid by its predecessors.

In fact, if one looks at the past three administrations — Obama, Trump and Biden — there is a certain continuity on many major cybersecurity issues. At the Department of Defense, overarching strategies like persistent engagement and the build-up of mission forces at U.S. Cyber Command have seemingly chugged along regardless of who occupies the Oval Office. So, too, has CISA’s rise in prominence to the lead agency for civilian cybersecurity and one of the government’s most credible conduits of outreach to the private sector.

The tail end of the Obama administration marked the beginning of cybersecurity as a major policy issue, starting with the 2014 Sony Pictures hack and the 2015 Office of Personnel Management hack. The ability of states to groups to bring major players in government and industry to their knees through cyber attacks prompted leaders to pay closer attention to the way that software and hardware vulnerabilities could be exploited to achieve larger geopolitical goals.

The creation of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the steady buildup of U.S. Cyber Command’s 133 mission force teams, a more aggressive posture towards China’s global telecommunications presence, new cybersecurity requirements for defense contractors and a broad reevaluation of how data localization laws influence policy in the contracting and supply chain space were all realized during the Trump administration. While some of these developments were in the hopper well before 2017, they were also often blessed and supported by White House officials and political appointees.

There is one major point of discord between the three: the failure of the Trump administration — and Trump personally — to robustly confront Russia on its wide-ranging offensive cyber operations to conduct espionage, meddle in U.S. elections and steal military secrets and valuable private sector intellectual property. It’s widely viewed as the greatest cybersecurity policy failure of the administration, yet even here, components of the U.S. government gradually ratcheted up cyber-related economic and military sanctions on Moscow throughout Trump’s term.

Despite different ideologies and styles between the three administrations, Spaulding agreed that there has been a strong degree of continuity on cyber policy across all three administrations. What has been missing is the kind of prioritization of the issue in the White House that can centralize strategy, break through bureaucratic turf wars and imprint on the work being done at individual agencies.

“My sense is that [during the Trump administration] each of the departments and agencies did as best as they could to move forward on the mission,” Spaulding said. “What was really lacking was that top-down leadership of the interagency, to do whole of nation planning.”

Under the spotlight

While it’s true that mandates around multifactor authentication, information sharing and other activities are widely considered low-hanging fruit and not sufficient to meet the threat from modern advanced persistent threats (APT), they’re also necessary building blocks for any effective security program.

The administration has also moved to expand and the tracking and harmonization of cybersecurity data and telemetry from its endpoints, something that could have subtle but large impacts on the way that information can be shared with other agencies and industry to detect attacks and attribute hacks to foreign nations and other actors.

Emily Harding, deputy director for the international security program at think tank CSIS, told SC Media that the administration’s approach in its first year in office has been promising but that it’s “way too early to tell” how many of its moves on cybersecurity will pay long-term dividends. She highlighted the specific roles and collaborative natures of Inglis and Neuberger, as well as industry outreach efforts like the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative, as key components of success.

“I think a year from now if the JCDC is still doing really great things, if the combination of Anne and Chris have been able to continue to conversation with the American people about cyber hygiene issues and continue to develop their relationship with the private sector where we’re all rowing in the same direction, that would be a success in my mind,” she told SC Media.

Capdevielle posited that while the public and politicians may be paying more attention to the issue these days, it’s often not handled in a thoughtful or planned out way.

“When you have things like Colonial Pipeline and voters get their gas disrupted, or their meat disrupted, or voters get scared because of the water hack in Florida, people become reactive to those things versus strategic or proactive about other things,” he said. “We can’t be proactive or strategic when 100% of our energy is consumed by what the voters perceive they want versus what a smart government may do proactively for them.”

Where some see this reactive posture as a bad thing, others see a healthy and newfound awareness by policymakers that these issues have real impact on their communities and must be addressed lest they lead to fallout in the public or political realm.

Spaulding pointed to the Colonial Pipeline hack as a primary example of how cybersecurity was able to break through the noise and enter mainstream discourse, as families discussed how a (consumer-created) gas shortage in the wake of the attack might affect their life.

The political will comes about as a result of incidents,” Spaulding said, adding the pipeline incident “was galvanizing because it got the public’s attention … because it became an issue that members of Congress had to anticipate being questioned about at Town Halls. They suddenly got religion.”

This is part of SC Media's special October coverage, in honor of Cybersecurity Awareness Month, spotlighting “security by design”: How different organizations within various verticals recognize their own security practices not only as a necessity, but also as a differentiator. Click here to access all of our security awareness coverage, which will filter out throughout the month.