COVID-19 contact tracers are reportedly having difficulties alerting individuals who have been exposed to the coronavirus, because some of the people they are calling refuse to answer out of concern they are being scammed.

This public health risk exemplifies a hidden cost of the fight against phishing and vishing scams: lost time and business inefficiencies caused by paranoid employees who filter out legitimate communications.

“People aren’t opening everything… They are rationally resisting approaches that they can't figure out how to trust,” said Peter Cassidy, co-founder and secretary general of the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG). "It’s making life hard for the bad guys. But it's making things impossible for [efforts] like public health initiatives" or certain corporate communications.

So how do public and private sector organizations ensure people strike the right balance? There are at least a few steps that callers, email senders and the message recipients themselves can take to reduce the odds that an important communication is missed due to phishing fears.

Too much of a good thing?

Employees are trying to avoid suspicious emails and phone calls, and rightly so, as they can result in malware infections and business email compromise attacks. But hyper-vigilance also has its drawbacks. And it’s not just people refusing to respond to calls or emails.

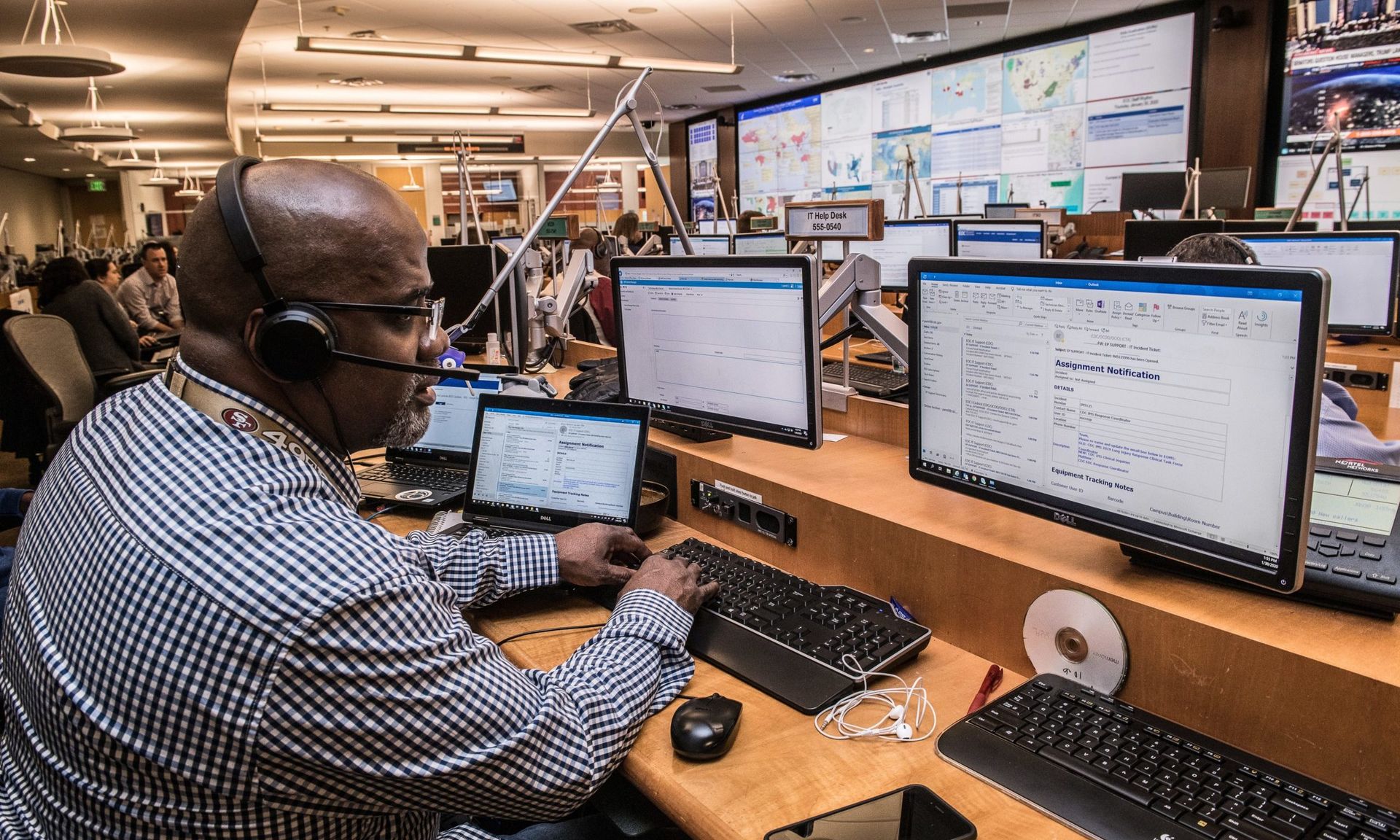

“The other side of it is internal security teams… are getting flooded with all these emails, because people think they're malicious and they're sending them into their SOC,” said Crane Hassold, senior director of threat research at Agari, and a former analyst with the FBI’s Cyber Behavioral Analysis Center (CBAC).

The problem is that real communications and fake ones are getting harder to distinguish from each other. Attackers use current events as a trigger for people to engage, which has indeed led to a scourge of COVID-themed phishing scams since the pandemic started. Recipients are flooded with lures related to coronavirus maps, vaccines and, yes, contact tracing, to trick people.

That forces legitimate contact tracers to fight through that noise. And the tactics raise flags. “I don't know about you, [but] I have never gotten a text from the local health department in my local jurisdiction," said Joseph Blankenship, vice president and research director, security and risk at Forrester Research. "If I got one, I would probably immediately be suspicious.”

Hassold calls it a double-edged sword, where security professionals have successfully conditioned people to look out for potentially malicious messaging, but serious communications that may use similar themes as bad actors get ignored. The IRS is another organizations that is constantly impersonated by hackers, and as a result, may not be trusted when sending bona fide communications. And the skepticism extends to the corporate world, which can sometimes send emails to engage potential partners, clients or consumers that sound a little too much like the bad guys.

"It's really difficult,” said Hassold. "Especially if it's an unsolicited email that someone's not expecting. You need to grab their attention in some way, but a lot of those ways that you would grab someone's attention are the exact same tactics that a cybercriminal would use in a phishing email.”

“Now you understand the pain of the marketing department,” agreed Cassidy.

Blankenship also noted how certain older encrypted email services used by health care providers and other organizations to remotely convey sensitive information send messages that “looked like a phishing email” to the average recipient. “Click on this and you will be able to get your x-rays or your medical report.' You're like, 'yeah right,'" he said.

Consequently, Blankenship hears from insurance companies, both on the healthcare payer side and on the casualty and property side: "‘How do we create a better experience for our users, so it actually looks like us?' We train our users not to click on things that look like us, that aren't us, and now we actually need to make [messaging] look legitimate for a good customer experience.”

Strategies for regaining trust

There are ways to cut down on the number of calls and emails that are wrongly rejected as spam, but a lot of the onus is on the senders to make their communications look as credible as possible. For starters, companies can implement domain-based message authentication, reporting & conformance, or DMARC, a protocol designed to protect their own email domains from being spoofed.

DMARC works by authenticating an email sender’s identity using DomainKeys Identified Mail and sender policy framework standards. DMARC users also set a policy for whether emails that don’t pass validation should be rejected or quarantined or allowed by the email servers that receive them.

But DMARC is not a panacea. While it blocks certain spoofed emails before reaching the recipient, adding an extra level of security for users, those emails that arrive in the inbox could still be ignored out of fear.

“It doesn't really address authentication at the user level. It's supposed to keep us from ever seeing something that's not authentic,” said Cassidy. But it fails at “satisfying the needs of someone [looking] to authenticate a communication.”

There's also brand indicators for message identification, or BIMI, an emerging specification standard that allows companies to display their branded logos within emails that are sent to participating inboxes. The email must pass DMARC authentication checks for the logo to be displayed. This provides the recipient with additional confidence that the message is truly from the sender, said Blankenship.

Additionally, email or SMS senders may want to give their email recipients a secondary, “out-of-channel” option to contact them rather than directly replying. For instance, they could suggest contacting a publicly listed phone number. “

And you arrange to have an extension [set up] for you, so that inbound calls can find you,” said Cassidy. “Or tell them to place your name on the switchboard” so they can ask for you by name.

Whatever the confirmation process is, “it's got to be one step,” he added. It must be a simple process that doesn’t require a “great effort” or for the recipient to jump through multiple hoops.

Another advisable tactic: Don’t rely on attachments or links. If you’re sending a press release or company communication, place the entire content within the body of the email so the recipient isn’t forced to open a document or click a link they don’t trust.

"Having everything text-based is a great way to lessen the anxiety and the uncertainty,” said Hassold. “If you don't have to click on a link or open an attachment, I think you've just mitigated a lot of the potential threats in that email.”

From a recipient’s point of view, companies can do more to help them distinguish between genuine and fake communications through a combination of better security training and email security solutions that filter out most phishing scams before they ever reach an inbox.

“Security awareness training is great to get people conditioned to look for obvious bad stuff,” said Hassold. And then boosting those efforts with internal security controls that detect and eliminate scams increases trust in the emails that do arrive, since employees “don't have to go through this super intensive review cycle, to make sure something's legitimate. If they get something that checks all the boxes that makes it legit, then they can probably open it and feel safe.”

But the question remains: Just how big of a problem is the misidentification of legitimate communications as scams? It’s hard to tell. The experts who spoke with SC Media were unable to cite any known studies that have attempted to quantify what percentage of genuine calls or emails are going unanswered due to suspicions of phishing, or how that translates into lost time and revenues.

Blankenship said that if they were to look into this topic, a survey would be a good place to begin.

“And then we would hope that people would actually open survey and take it.” Which, clearly, is no guarantee.