Finding a needle in the proverbial haystack seems absurdly simple compared to managing security information and event management (SIEM) systems. How can you find that blip of an anomaly that indicates a bad actor just launched a piece of malware or impersonated your system administrator when your log files are the moral equivalent of finding a black-stripped zebra in a field of white-striped zebras?

Essentially, today’s security operations team is looking for that errant log entry that will make the difference between a megabreach that could cost your company millions and steal your data or simply redirecting an intruder into a honeypot where they can peacefully peruse bogus data while you lock the back door and get ready to crush the intruder.

That’s why SIEMs, central to enterprise-class security operation centers (SOCs), are increasingly used not just to parse through data after a threat is a discovered, but also to inform incident response teams of threats before or as they happen.

By combining three elements — savvy integration with other tools, greater operational expertise, and steady technological advances — security professionals can use SIEMs to better separate the threatening signals from the mundane noise of legitimate user activity and network traffic, experts say.

And if technicians in the SOC can build alliances with applications teams and IT infrastructure groups, they can boost a SIEM’s ability to distill information about potential threats simply by excluding background activity at the outset.

Bring the noise

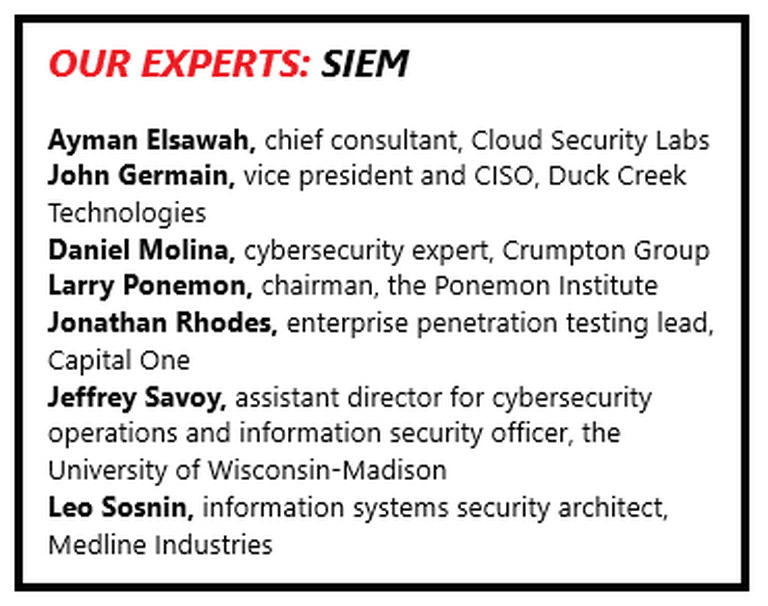

SIEM took the cyber defense world by storm in 2005 because it offered a powerful way to pull together disparate logs and speed SOC teams’ efforts to move from analysis to action. But the success of SIEM brought a new challenge: how to find the meaningful data amid the information now funneled into the system by a constantly growing number of cyber tools. The result is pressure on SIEM providers to innovate, which is happening, says John Germain, vice president and CISO at Duck Creek Technologies of Boston, a software provider to the insurance industry.

“I have seen SIEMs mature from the perspective of giving operators better options to consume and filter logs from disparate sources, allowing them to decide what is noise and what is relevant and then being able to turn off the noise unless it is needed,” Germain says. “The key improvement area that I have seen is the incorporation of threat intelligence as part of the event correlation and the linking of identified threats to CVEs (common vulnerabilities and exposures). This type of crowd sourcing of threats helps identify risks quicker.”

Nevertheless, SIEM’s ability to filter and discern different types of potential threats must be constantly updated in order to handle input from a wide range of sources, including endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools, end user behavior analytics (EUBA), and file integrity monitoring (FIM).

The issue, says Ayman Elsawah, who runs the Cloud Security Labs consultancy in San Francisco, is whether to keep using SIEMs in their original function as a log aggregator while using EDR and EUBA for alerts, or building out the SIEM platform to serve as the proverbial single pane of glass.

SIEMs ultimately are dependent on the kinds of information they ingest and how SOCs are trained to respond. Thus, the first challenge cybersecurity professionals face is deciding what to pull in, how to establish a baseline pattern to track normal network traffic and user activity, and tuning it all to enable rapid response — all in the context of information that increases by the day.

“Default rules and alerting for SIEMs might have gotten a little better over the years, but what may be noisy to one customer isn’t to another,” says Jonathan Rhodes, enterprise penetration testing lead at Capital One. “Baselines and tuning are still a must when implementing any SIEM. Every customer will have something unique that will need custom rules and alerting as well.”

The push for more endpoint agents and tools to pump up SIEMs stems from experiences of early adopters who struggled to integrate the platform into their security operations, says Larry Ponemon, chairman of the Ponemon Institute, the information security research organization based in Traverse City, Mich. The inputs often outpaced the number of personnel able to operate SIEM platforms effectively, he says. But the picture is changing. “SIEM is coming forward with artificial intelligence (AI),” Ponemon says, as organizations realize that “they need something to find the needle in the needle stack.”

chief consultant, Cloud Security Labs

Still, a gap remains between the goals established for SIEM and its implementation so far, Ponemon says. According to the 2017 Ponemon Institute survey Challenges to Achieving SIEM Optimization, some 76 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that SIEM was important, but just 48 percent reported that they were satisfied. Their wish list: better correlation of data, including third-party feeds, improved forensic analysis, and better automation.

The survey’s conclusions are likely still valid, Ponemon says, as many organizations are still looking for ways to improve SIEM to meet their goals. In any case, the scale and complexity of the threats facing enterprise-scale organizations leaves organizations no choice but to push ahead with SIEMs and try to improve performance, he says.

Teasing out the signal

Given the daily tsunami of inputs, some SIEM operators might be tempted to turn down the volume of log data ingested into the system. But taking a less-is-more approach to SIEM might miss the opportunity to leverage that data in new ways that can highlight actionable threat intelligence, says Jeffrey Savoy, assistant director for cybersecurity operations and information security officer the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

For example, by enriching log events through adding geolocation information to IP addresses, SOC teams can spot a potential adversary more rapidly, he says. The addition of data such as vulnerability management and risk ratings for assets “can assist in both the accurate identification and prioritization of alerts,” Savoy says.

Such a tactical, targeted approach to SIEM can yield other immediate benefits, says Capital One’s Rhodes. But first, SIEMs have to take in virtually every measurable activity. “Log everything,” he says. “Then create or tune alerts to fire on reliable — or mostly reliable — correlated events. There will always be some noise and false positives.”

Yet finding a threatening signal amid the ordinary noise cannot be left to technology alone, Rhodes says. “A good way to develop purposeful alerts is for the SOC to partner with purple and/or hunt teams,” he says. “Hunt teams can help identify IOCs (indicators of compromise) and other behavior to alert on.” Red team attacks on the SOC can help generate new alerts that the SOCs can correlate with the SIEM.

enterprise penetration testing lead, Capital One

Another way to separate anodyne log data from ominous indicators is to filter them at the source before they head SIEMward, says Leo Sosnin, information systems security architect at Medline Industries Inc., a manufacturer of medical equipment based in Northfield, Ill. For example, if the security operations team gets in step with the IT operations teams responsible for a systems configuration management tool, the SIEM could capture unexpected behavior on Windows endpoints more easily.

“A typical environment with a healthy (server-level systems management configuration application) or other type of management software produces a ton of PowerShell activity,” Sosnin says. For example, a security team might wish to log changes in configurations, compliance settings and more that, combined, can be quite noisy from a SIEM perspective.

There are two main ways to distinguish such activity from malicious scripts, Sosnin says. One is to “digitally sign all company scripts with an internal PKI (public key infrastructure) certificate, or just run them from a certain folder that is accessible for the (server-level systems management configuration application) local service account only, or both.” If PowerShell scripts run from the expected folder established by operations teams, it is likely to be normal activity. But if an unexpected script kicks off from within a user profile, it is suspicious.

“Because regular users can’t place anything into this folder, the bad guys won’t be able to trick the users to launch any malicious PowerShell scripts from there,” Sosnin says. His suggestion is to “strike a deal with the [server-level systems management configuration application] team to run their scripts out of [a specific] folder” so that everything else can be flagged in the SIEM.

Ponemon argues that to make SIEMs effective at capturing the right information, SOC leaders have to reach out organizationally beyond IT infrastructure and operations to application development teams. “You need someone in DevOps (development operations) to implement SIEM properly,” he says. “Politically, that is not easy. There are multiple sensors for endpoints, for example. And people in IT security get ticked off at IT Ops (IT operations) for not installing them correctly.”

Once cybersecurity teams successfully negotiate with operations and development teams, they have a range of options that need not be technologically complex to be effective and provide the SOC with an ability to be more calibrated in its approach, says Elsawah.

“This typically involves installing an agent of sort on the endpoint to gather logs, process information, and other metadata to put together a good story. There are open-source tools like osquery and OSSEC, but also third-party tools to help detect this behavior,” he says. “So having good data to begin with is essential, then tuning a SIEM to detect this behavior is the second part.”

Turning up the tech

Sorting out obviously irrelevant data can set up the SIEM to better meet its stated purpose: analyze event data in real time to speed investigations and provide good forensic evidence. Many organizations have “used SIEM to normalize their monitoring floor but they haven’t used it to correlate between multiple tools and to understand what is truly relevant,” says Daniel Molina, a senior consultant with the Crumpton Group, a global strategic advisory firm, based in the Miami area.

and information security officer, the University of Wisconsin-Madison

Ponemon agrees. Making use of such correlations is a years-long process as organizations slowly learn how to integrate technologies such as next-generation firewalls, he says. “The challenge is to use SIEM across the enterprise,” he says. “Can you integrate it with SOCs, not just people specialized in running SIEM?”

In this SIEM setup, more skilled operators and new technologies, such as machine learning, can give the SOC more capacity to respond to potential threats, Savoy says. For example, the SIEM might retain additional information related to the failure to assist an analyst in the event of a rash of failed login attempts.

“However, sometimes an analyst will still need to follow up with the user as the log events might not be enough,” Savoy continues. “Since this might be time intensive, hopefully the SIEM has information to map the account to the categorization of the system so that these investigations can be prioritized by criticality.”

Advocates of AI point to how such technologies can help deliver on the promise that SIEM offered earlier this decade. With machine learning, next-generation SIEMs can help analysts spot patterns and identify potential threats with a speed and accuracy that is impossible for humans running older SIEM platforms.

Whether or not to pursue such an approach depends on the SIEM’s capabilities and configuration and capacity, says Rhodes of Capital One. “Depending on the how the data is added, an analyst may choose to see only this additional information in small time slices or just the hits on keywords as needed,” he says. “However, in the past, I have found that it can be important to prioritize what events are put into a SIEM since there are often capacity limits and performance hits with ingesting a large amount of unstructured data.”

Even so, a machine-learning SIEM can be expected to coexist with human-run SOCs while relying on the SIEM for more targeted automation, says David Monahan, managing research director for security and risk management at Boulder, Colo.-based Enterprise Management Associates.

“While something like 96 percent of organizations are fully on board with fully automated [incident response], only about 18 percent were on board with fully automated [incident response] due to distrust that it could mistakenly cause issues resulting in negative impact to the business,” says Monahan.

Still, many users expect, or at least hope, that such technologies could bring fundamental changes. “I find it takes a good amount of staff resources to tune and maintain a SIEM to extract the most value” says the University of Wisconsin’s Savoy. “As the technology advances, I will be interested in learning how features like machine learning will help automate some tasks and help identify more sophisticated attacks.”

For now, the increasing affordability and usability of data analytics will allow SIEM operators to crunch through events on a scale that no human can handle. The correlations that emerge can enable SOCs to take action sooner. “The events are already in SIEM; it’s just nobody analyzes them at this point,” says Sosnin.

That is why SIEM’s success might not come in a big bang, but rather through evolutionary development with AI and machine learning improving performance. “You’ve got a new generation of technology, a new skill level in personnel, and new cloud capability,” says Ponemon.

But that will require a new approach by cybersecurity pros who have used SIEM as the axis for an endless series of new tools. “We’ve simply automated bad decisionmaking,” says Molina. “But I think we are on the path of getting it right because we have to.”

SIEM in the era of cloud

The unstoppable momentum of public cloud computing has further complicated the challenges of effective a security information and event management (SIEM) implementation.

First installed on premises in very large enterprises, SIEMs now straddle the legacy data center as well as cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud. And with SIEM-like services available in both infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) and platformas-a-service (PaaS), organizations still have more to log and correlate — not just legacy servers and storages that were lifted and shifted to the public cloud, but also cloud-native technologies such as containers and functions-as-a-service (FaaS) technologies like AWS Lambda.

“A lot of companies took the approach that it is easier to split SIEM — one in cloud and one for on prem,” says Larry Ponemon, chairman of the Ponemon Institute. “That was a big mistake. They need it integrated across the enterprise. You are talking about terabytes of data.”

Daniel Molina, a senior consultant with the Crumpton Group, says the cloud might provide better scale for SIEM. Yet the core tasks facing SIEM operators — ingesting ever-growing amounts of log data and using it to empower security operation centers (SOCs) —remain. The move to the cloud simply “changes the ZIP code” for the SIEM, he says.

While leading SIEM providers have long been cloud capable, SOCs must still learn to tailor those products to handle the particular sorts of logs generated by public cloud providers, says Ayman Elsawah, who runs the San Francisco-based consultancy Cloud Security Labs.

AWS gathers the log data log into an S3 bucket, which can be accessed via a key provided by AWS identity and access management tools and funneled into the SIEM. Those logs must be parsed alongside traditional infrastructure. “We’re beginning get a lot of noise and false positives” from cloud logs, Elsawah says.

To parse such log information effectively, SOCs can use cloud-native tools such as role-based access control (RBAC) to dynamically get access without having an access key that could become vulnerable, Elsawah says.

Microsoft includes a variety of logs, including control plane activity, diagnostics, Active Directory, virtual machines, and storage. It also has a log integration function that sends data to an on-premises SIEM.

For its part, Google has a logging agent and a log viewer that can ingest AWS log and provides integration with various SIEM offerings.

But while the cloud can help ease many SIEM challenges, the incident response teams’ jobs are unlikely to change much as a result. It’s a tool,” says Elsawah. “At the end of the day, you need good SOC analysts who have the ability to find this nuanced behavior. That takes a combination of skill, grit, persistence, and opportunity.”