There’s a certain amount of pressure that comes with being a security reporter and agreeing to get scored on a phishing test for all to see.

Granted, in real life, you never know when you’re being tested by real-life cybercriminals trying to get you to click on a link or open an attachment. That can happen any time. But it was nevertheless reassuring to learn that I scored a nine out of 10 after being quizzed on whether a sample email was or wasn’t a phishing attempt.

Devised by email security company GreatHorn and security awareness firm Inspired eLearning, the quiz was taken by 1,123 U.S. users in September 2020. And that’s where the bad news comes in: Most test-takers fared a lot worse. According to GreatHorn's 2020 End User Phishing Report, the average test score was 52 percent. “So slightly better than a coin flip,” said GreatHorn founder and CEO Kevin O’Brien, in an interview with SC Media.

O’Brien walked through the 10 email samples, explaining what clues test-takers should have picked up on, including a few that even my own keen editorial eyes missed. Feel free to play along.

According to the CEO, the phishes were lifted directly from real examples. “We process an average of a bit over a billion emails on a heavier month… so what that means is that we have access to just an enormous amount of real data,” said O’Brien. “So we did draw from real phish, based on what we've seen.”

Let’s get the embarrassing part out of the way and start with the question that tripped me up.

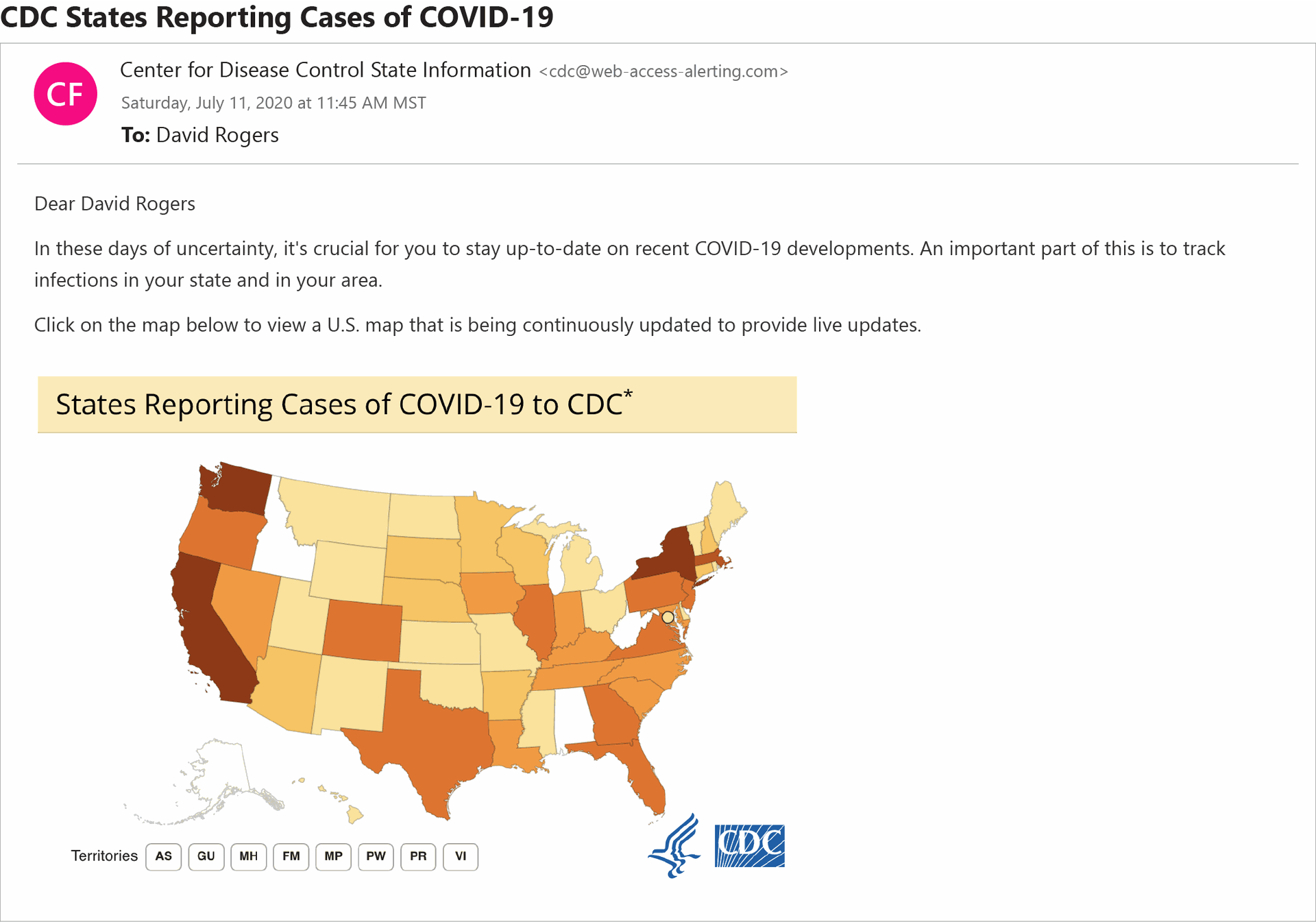

First, a disclaimer: I know there have been tons of COVID-19 scams since the pandemic swept across the world. And I personally would never open up an unsolicited email that supposedly comes from the CDC and encourages me to click on a map for the most recent coronavirus developments. But the above email legitimately looked as if could have come from the agency, and I couldn’t find anything wrong with it. I wondered if perhaps GreatHorn was trying to throw me a curveball by showing me a genuine CDC email.

It wasn’t. It was a scam. And I missed a key, subtle clue: “The only thing that should point out to you that it wasn't right is the return path,” said O’Brien. Indeed, the sender’s email domain appeared as cdc@web-access-alerting[.]com. “The CDC [sends] emails from cdc.gov,” the CEO noted.

“You’re writing for SC. You follow security. You write about phishing, and you’re taking a phishing test. So you're already thinking about, ‘Well could this be or couldn't it be?’” O’Brien said to me. “You had all the right questions in mind – and you fell for it. That is not unusual.”

In fact, nearly 52 of respondents incorrectly guessed that this was not a phishing email.

I was kicking myself for getting it wrong, spoiling what could have been a perfect score, but O’Brien was more forgiving. “That’s not one that's riddled with spelling mistakes and grammatical errors. It was well-written. And it's very compelling,” he said.

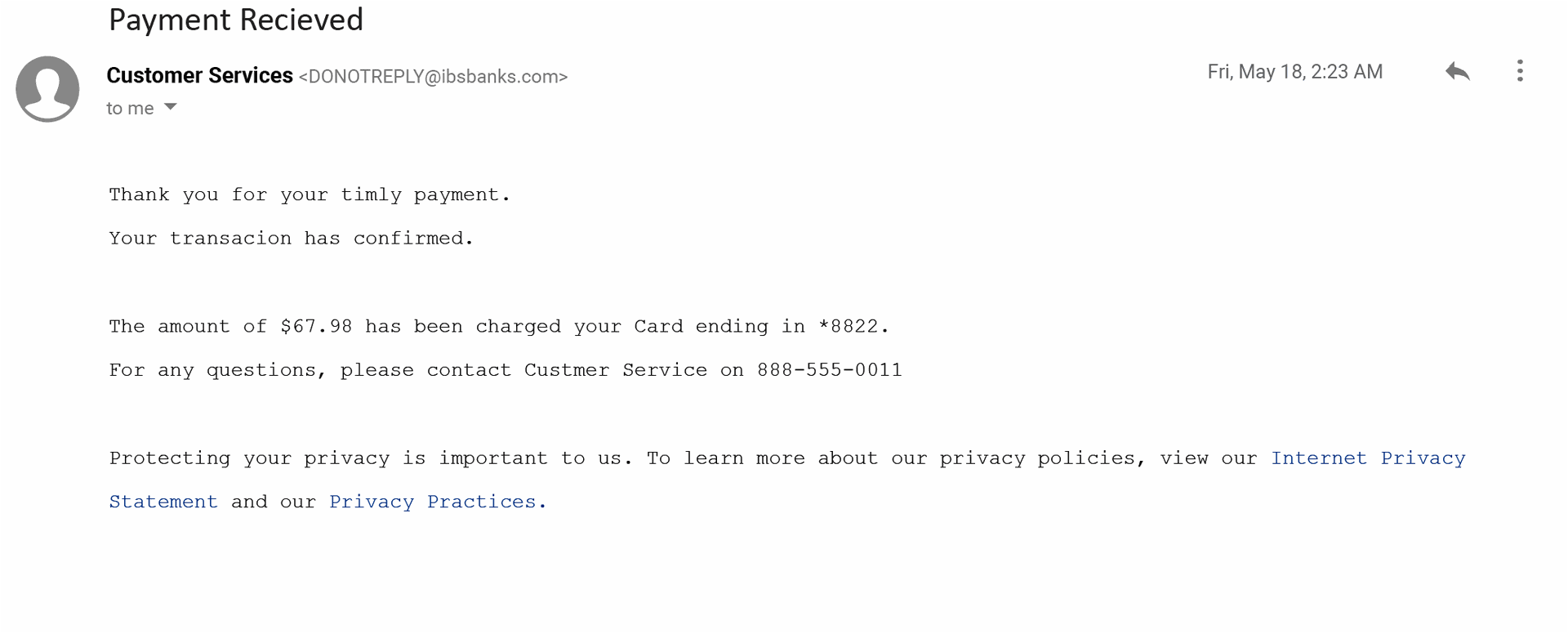

On the other hand, some phishes were so riddled with goofs, they were quite easy to spot, Including this email, purportedly from a bank, that said “Thank you for your timly payment. Your transacion has confirmed.”

Then again, maybe it wasn’t so easy: only about 51 percent of test takers labeled it a phish.

“That was a really obvious example of what should look like phish,” said O’Brien. And yet, “people did not do a good job of catching it.”

The reason: “Our brains are wired to correct errors in the things that we see and read,” said O’Brien. In real life, perhaps even fewer people would have caught it, because many workers are busy and distracted, or see an email about financial matters, which triggers a panicked reply without first stopping to think.

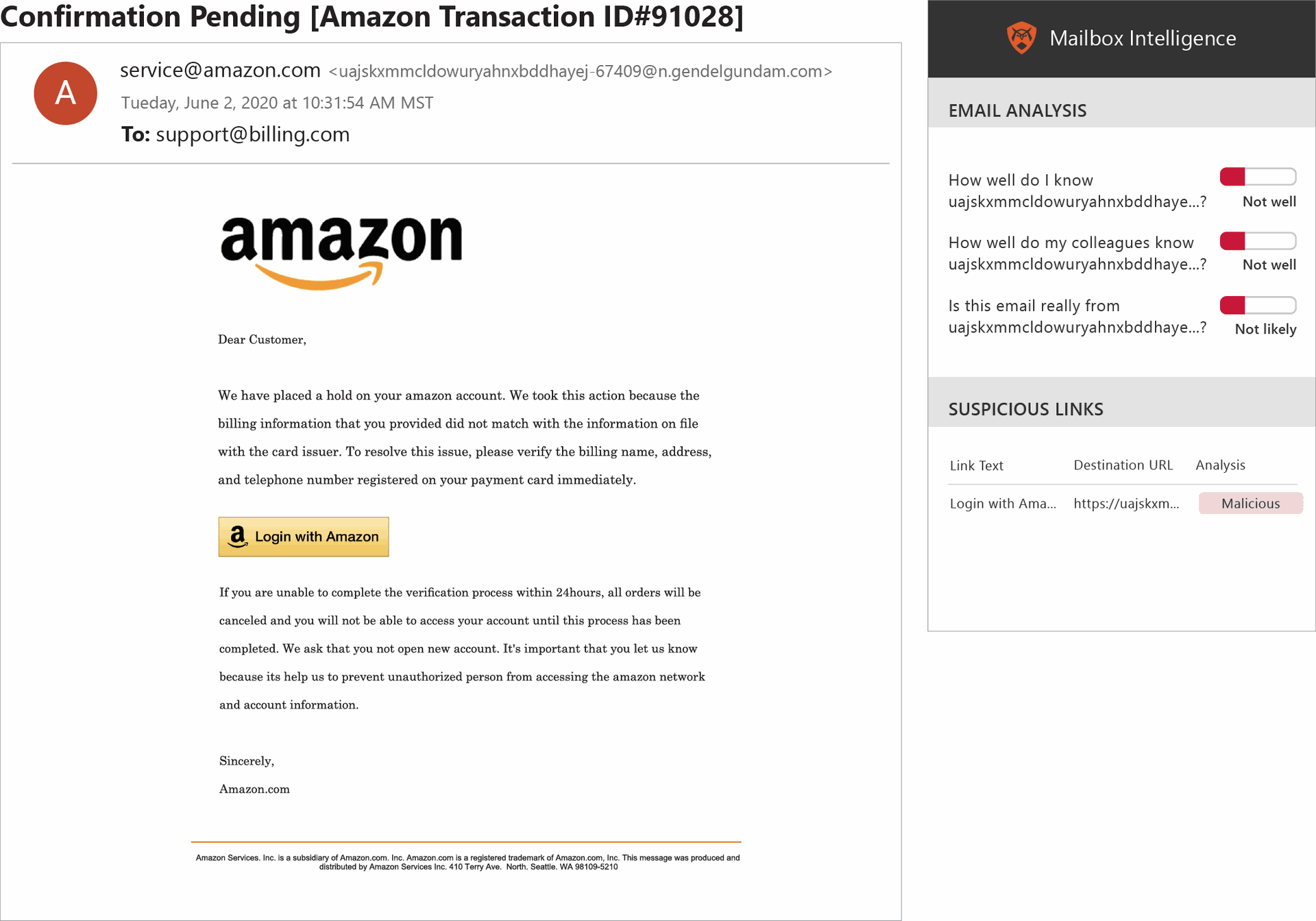

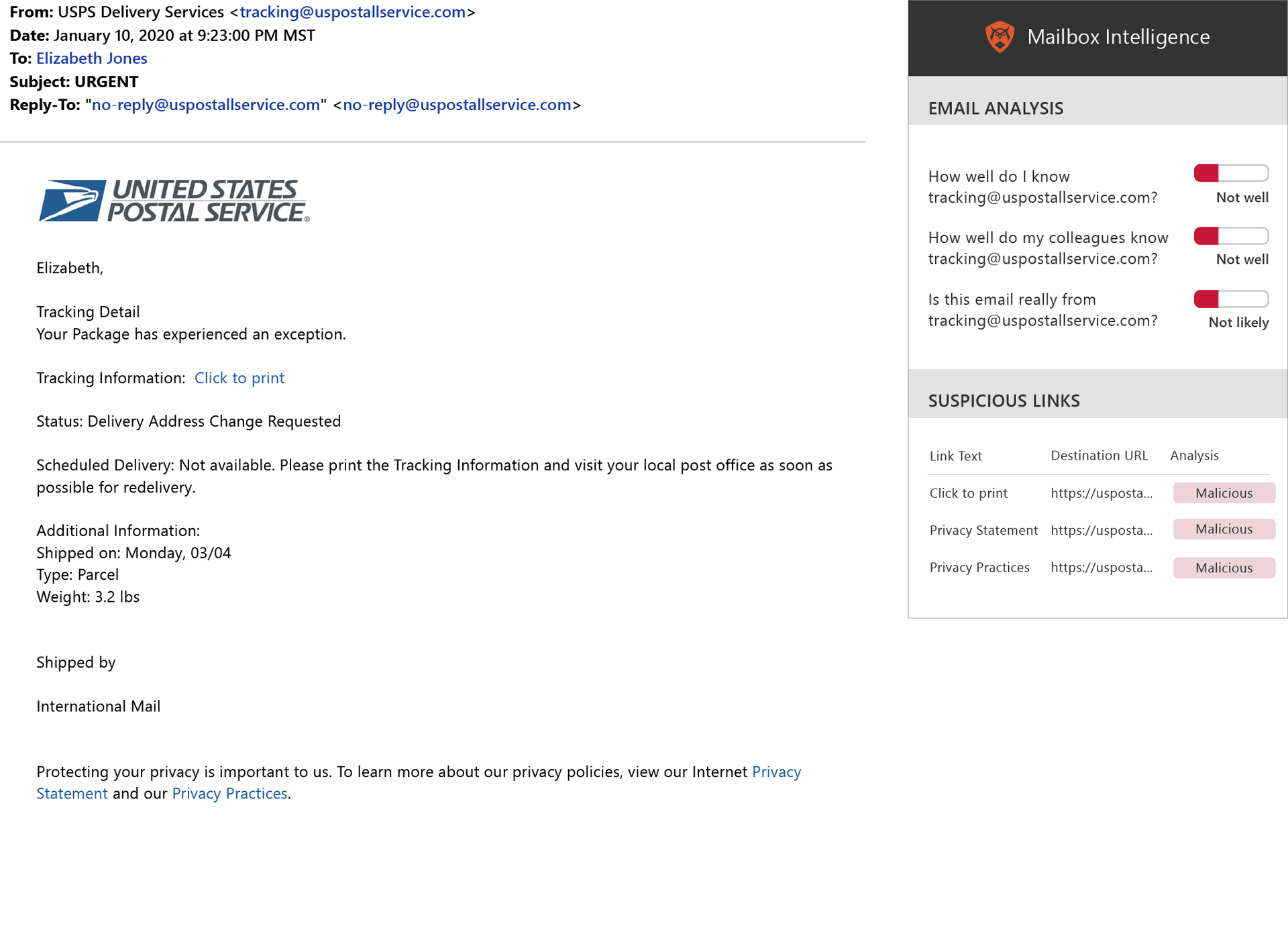

Despite whiffing on the CDC email, I was at least able to spot a few other suspicious envelope sender addresses that tipped me off to a phish, including a fake Amazon return path that featured a crazy, long string of letters and numbers, and a U.S. postal service address that I assumed should have ended in usps.gov but was instead suspiciously displayed as tracking@uspostallservice[.]com. (I am ashamed to admit I didn’t even notice the extra “l” in the address until O’Brien pointed it out).

The postal service one is particularly interesting because it encapsulates a common problem: mobile users are less likely to spot a phish than desktop users. This is due to factors like screen size and also because mobile devices are “increasingly used for quick actions to scroll and click, versus the more focused actions taken on desktop usage,” the report states. In real-life phishing scenarios, another problem is that email clients for mobile devices typically don’t show the full address of a sender, O’Brien added.

In the USPS case, 71 percent of desktop users correctly called it a phishing email, while only 58 percent of mobile users gave the right answer – a 13 percentage point difference. Additionally, mobile users scored 13 percentage points worse than desktop users across the full questionnaire.

Meanwhile, the Amazon email turned out to be one of the easier questions: 75 percent of respondents identified it as a phish. “The biggest clue for me is you see this giant Amazon logo,” O'Brien said, which is a tactic that phishing scammers often use to make the recipient “feel comfortable.” However, in this instance, the logo is abnormally large, not to mention the inconsistent capitalization of Amazon in the body of the text.

In general fake emails from ubiquitous and popular brands such as Amazon were on average more likely to be identified as phishing attempts in the test, “showing that individuals are learning to have a more critical eye towards emails from trusted brands,” the GreatHorn report stated.

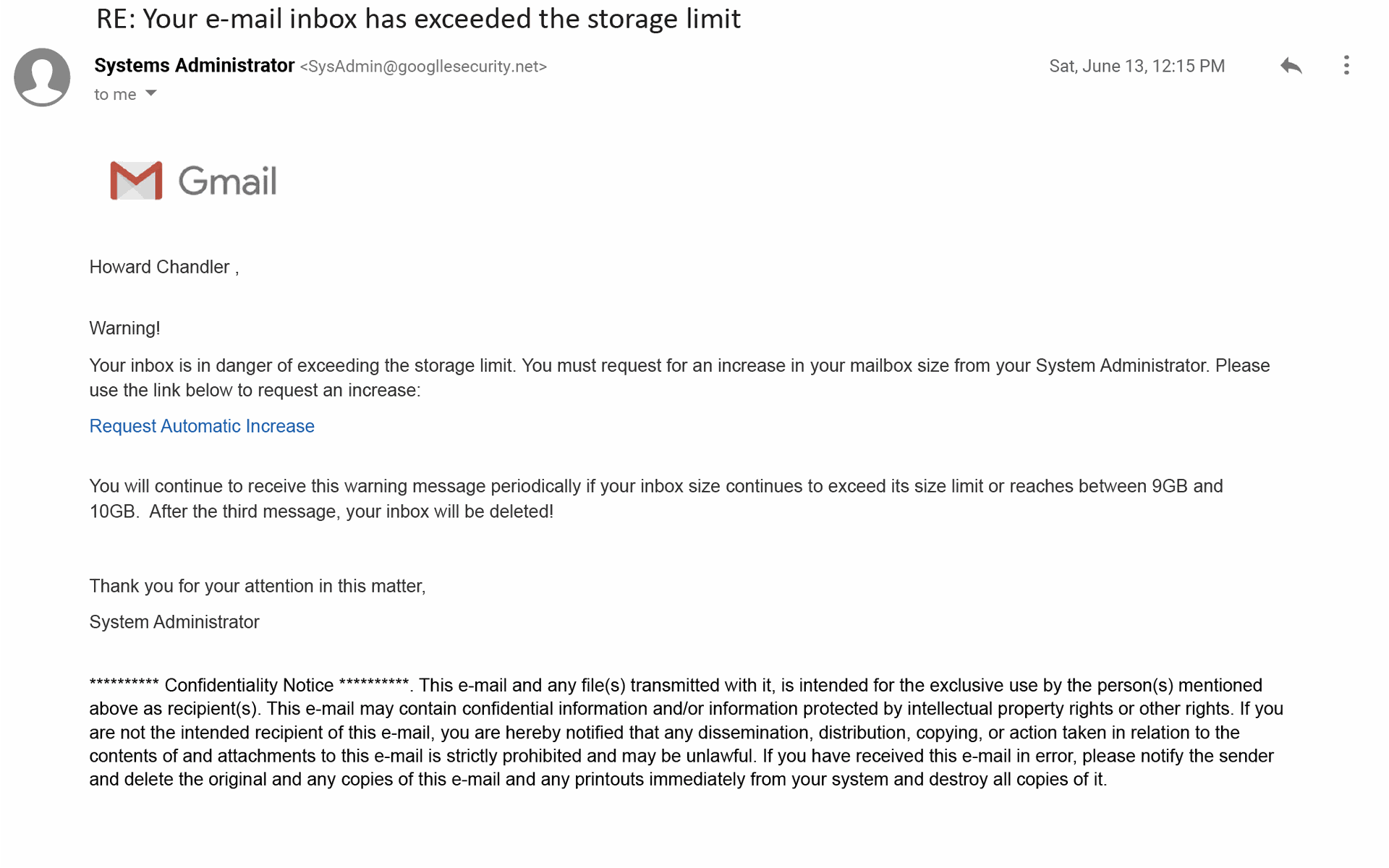

Case in point: a small majority of 66 percent identified the above Google-themed email as a phish. Like the postal service email, it contains an extra “l” in the sender’s address (Googlle.com). Additionally, its language was unusually alarmist and was signed, dubiously, by an anonymous “systems administrator.”

“Cybercriminals often use ‘Systems Administrator’ or ‘Service’ within their phishing emails, trying to disguise their attempted attacks as standard system warnings,” the report states.

“This one's easy mode,” said O’Brien, also noting the incorrect spacing after the salutation. “It's an obviously, ridiculously fake message.”

And yet, “people still fall for it.” Roughly 34 percent were fooled.

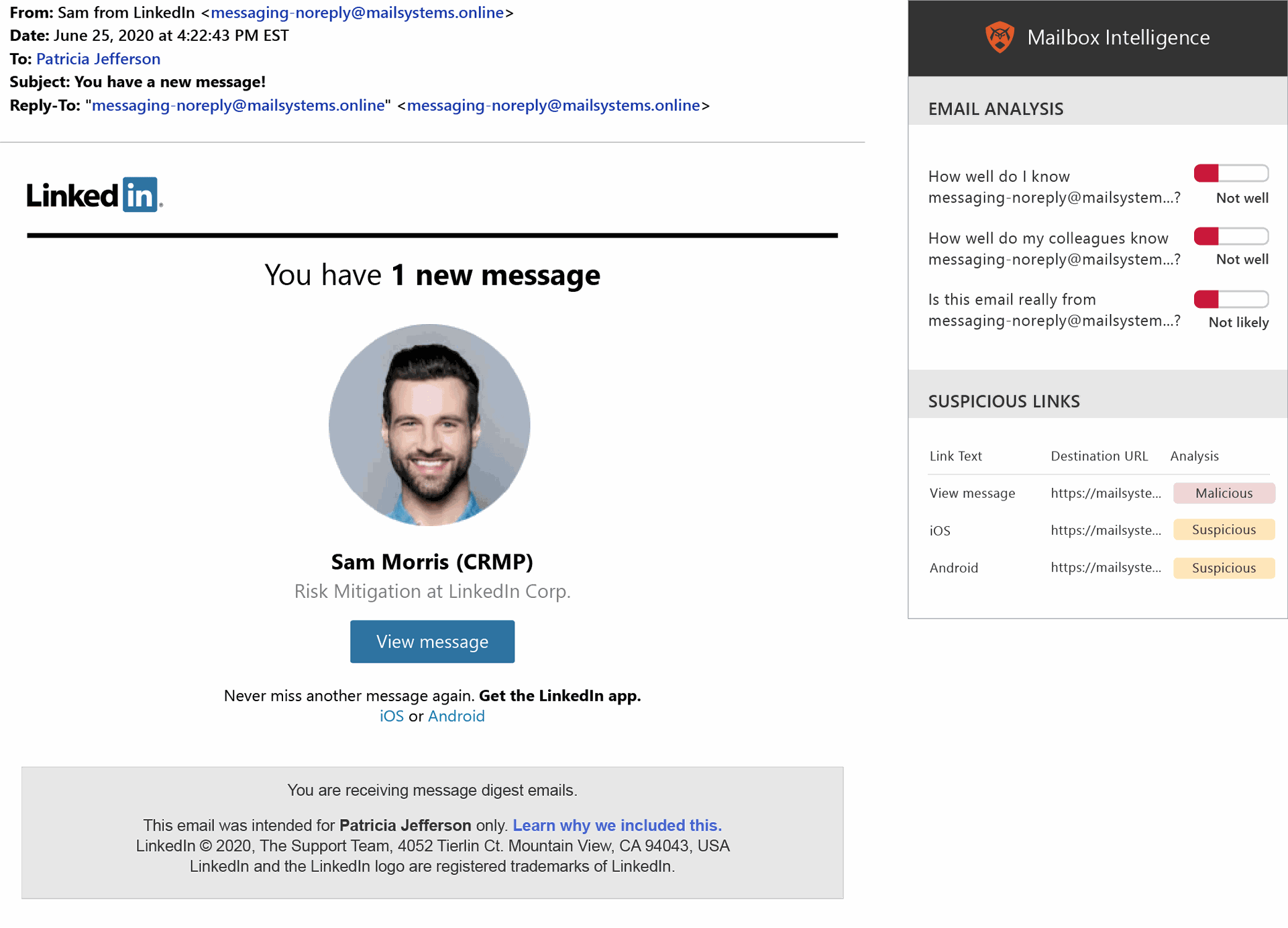

GreatHorn also quizzed test-takers with a LinkedIn email notifying the user of a message from a LinkedIn Certified Risk Management Professional. “The return path domain is not what it should be, but it’s got all of the hallmarks of how these brand impersonations work,” said O’Brien. “The logo’s there, the colors are right, it’s not ‘system administrator,’ and you probably get occasional emails from LinkedIn that looks kind of like this. So yeah, easy to get tricked.” Indeed, 41 percent were fooled and thought it was authentic, even though LinkedIn “does not send mail like this,” O’Brien added.

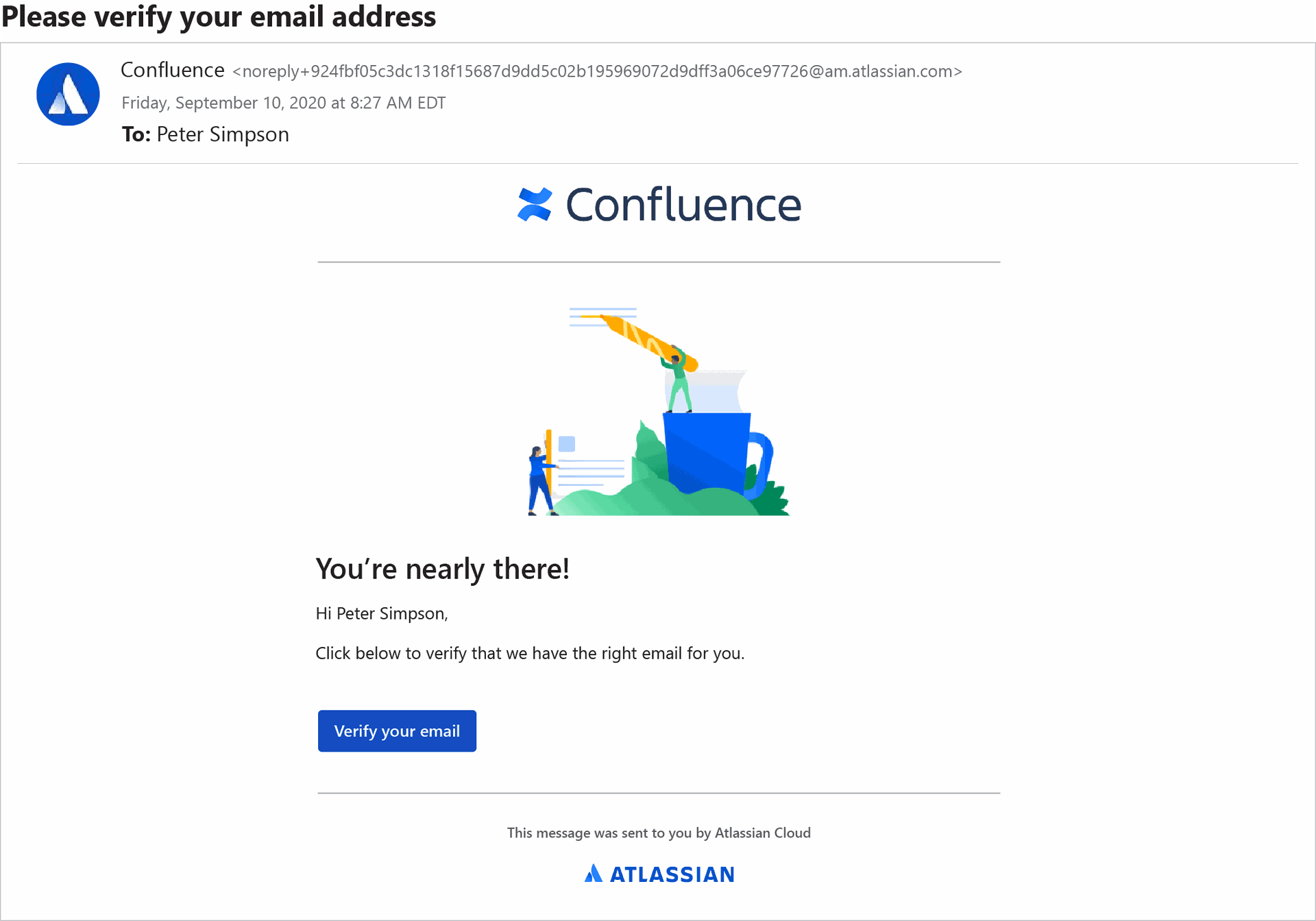

Among the categories of email that caused the most confusion were those associated with legitimate business services; namely, Confluence, Dropbox and Microsoft Teams.

The Confluence email looked to me like a verification email that I would normally receive if I were to sign up for the collaborative workspace service from Atlassian. Assuming that in this I did actually sign up, I correctly deduced that the email was legit. (Otherwise, why would I bother to open up the email in the first place?)

“Your instinct is right,” said O’Brien. However, a whopping 71 percent wrongly thought it was a phishing attack. The problem, he explained, is that sometimes workers receive this exact kind of email and mistakenly believe it’s a phish because their employer had set them up on the service without alerting them first. So the employees ignore the email, which results in productivity lapses.

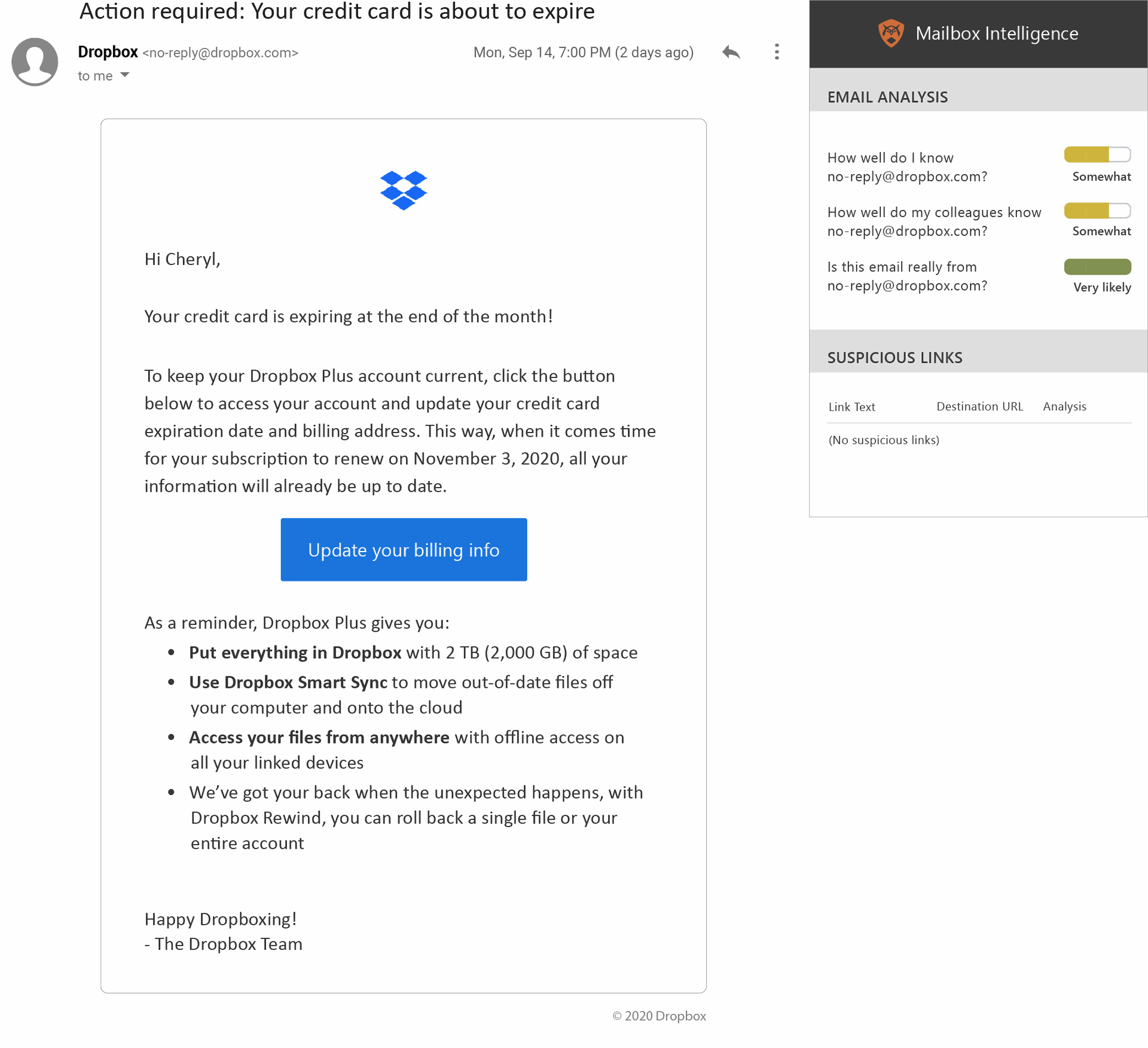

A similar legit email that threw off test-takers was the above Dropbox communication – 55 percent thought it was a phish, when it was actually legitimate. Again, in a case like this, failure to respond has its penalties – the user’s credit card will expire if action is not taken.

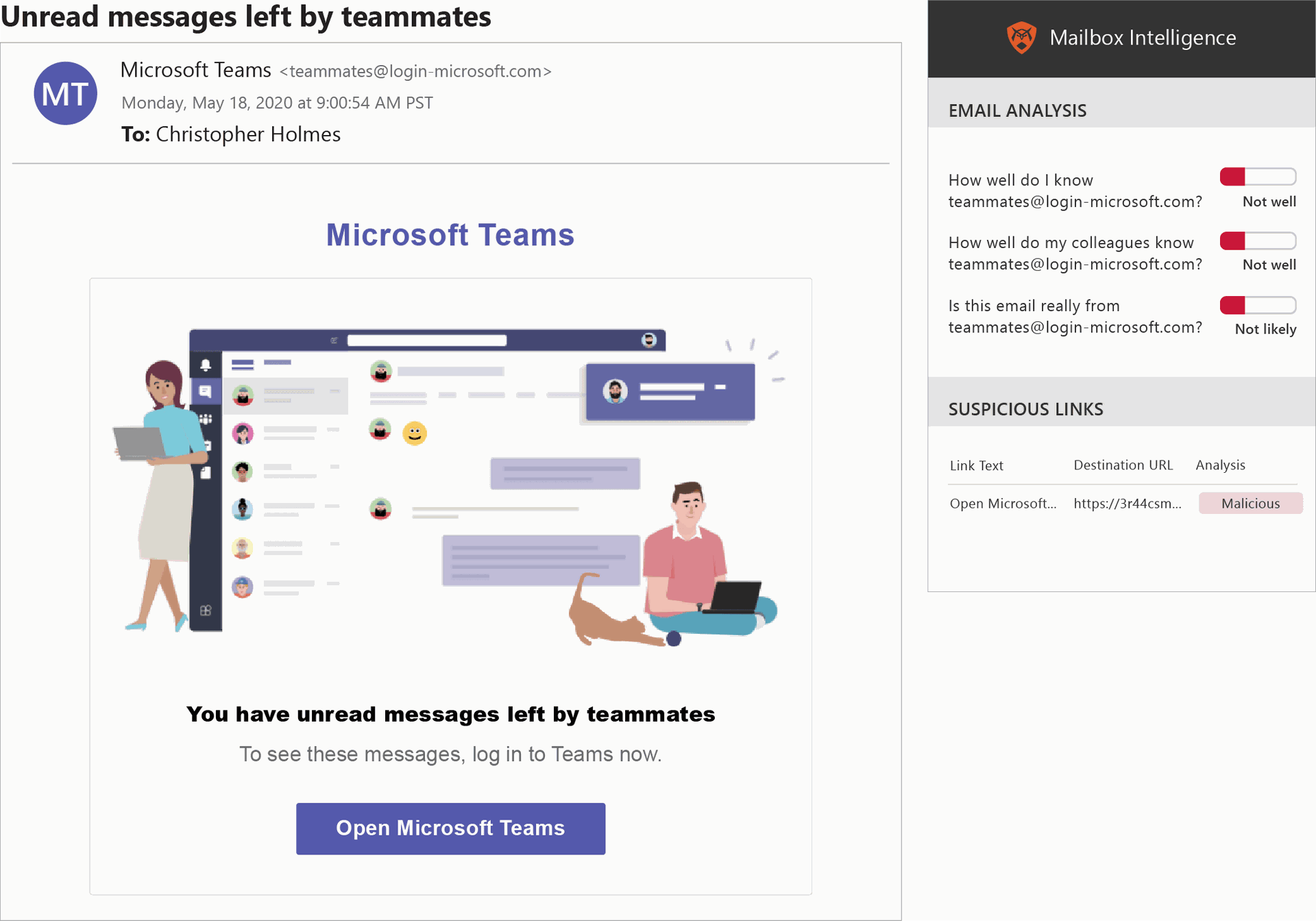

On the other hand, the above Microsoft Teams example is a phish – one that fooled 53 percent of the test-takers. Although the email looks professionally written, Microsoft does not use the address [email protected] to send these communications about unread messages. And while users can search online to see if a sender’s address is legit or not, “the likelihood that an end user is going to do that is zero,” said O’Brien.

There was a second Microsoft email on the test – an Office 365 one containing a password for a newly created or modified account. Respondents were evenly split, with 50.4 percent correctly guessing it was a genuine email, while 49.6 percent mistook it as a phish. “And it really highlights just how terrible authentic mail is,” said O’Brien. “Email is not a super secure medium, and part of why is that even with authentic messages, you're like, ‘I don't know.’”

For certain questions, the test randomly gave users additional helpful context by incorporating an image from GreatHorn’s Mailbox Intelligence plugin tool, which indicates familiarity with the sender’s email address, the likelihood that the email is actually from the sender, and the presence of suspicious links.

Simply by trusting the tool’s advice, test takers could have answered those questions correctly. On average, the tool gave users a 10 percent better chance of accurately guessing if an email was a phish or not. And had these people actually been trained to use and understand the tool, the scores would have been even higher, said O’Brien.

Certainly, employees can use all the help they can get. No one's perfect – not even this reporter, as my 90 percent score proves. And in real life it only takes one wrong guess to give you and your organization a much bigger problem than a little pop quiz anxiety.