Civil rights advocates have long warned that facial recognition technology was open to abuse by government efforts to identify and track protesters. Those fears were borne out several years ago when records revealed that law enforcement deployed the technology on people protesting the Freddie Gray incident in Baltimore.

Civil rights advocates have also warned for years that the technology could lead to a false arrest, interrogation, or worse. Now, that nightmare scenario has proven true as Robert Williams, a black man living in Michigan, was arrested for a crime he didn’t commit because of facial recognition technology police shouldn’t have had the authority to use. When he was arrested by Detroit police in January in front of his wife and two young daughters, Williams initially couldn’t figure out what was going on. But after 18 hours in detention, when officers finally pulled him into an interrogation room, they let slip that facial recognition had flagged his driver’s license photo as a match to an image of a shoplifter caught on a store’s security camera. The match was wrong, and prosecutors soon dropped the charges. The American Civil Liberties Union filed a complaint on his behalf.

What Williams and his family experienced was dreadful. But, in a sense, they were lucky: Williams was only arrested. For far too many black men, an encounter with law enforcement has meant assault or death at the hands — or knees — of police.

Williams was lucky in another way. It’s rare for police to reveal that they used facial recognition technology to identify a person for arrest. There are likely others who, like Williams, were falsely accused because of this technology, but simply didn’t know that facial recognition put them in a suspect pool.

This secrecy stands as one of the many reasons why unregulated facial surveillance has become so dangerous, and why lawmakers must immediately halt police from using it. As that happens, defense attorneys must press prosecutors to disclose whether and how facial recognition technology was used in their clients’ cases. The Constitution requires such transparency, and guarantees citizens access to government records necessary to mounting an adequate defense. Such access can shed light on the dangers of facial recognition technology in at least three ways.

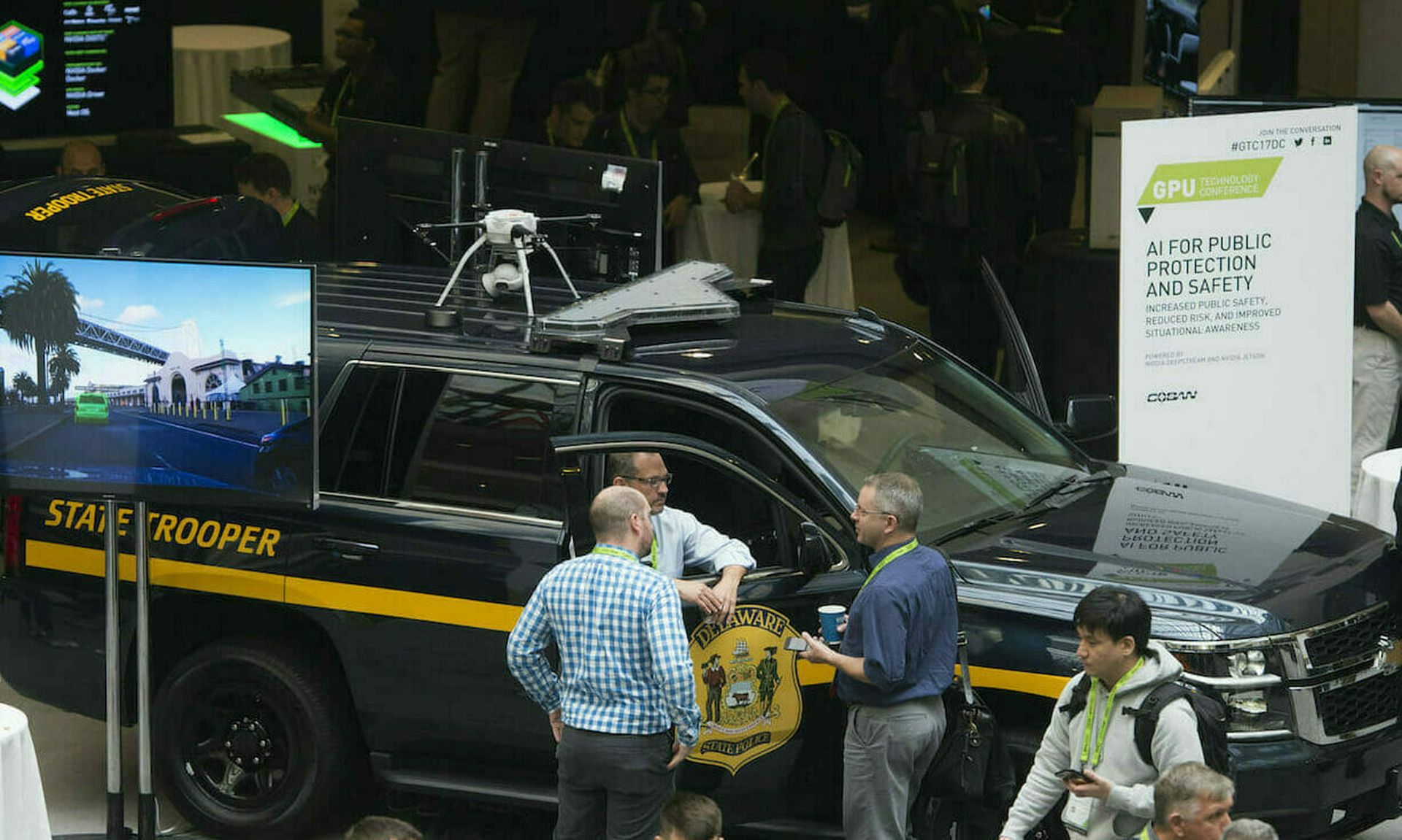

First, secrecy prevents judges, lawmakers, and the public from understanding the scope of the problem and ending abuses. We know thousands of law enforcement agencies across the country have access to facial recognition technology. But we don’t know how often they use it, in what kinds of cases, and with what safeguards. Are they investigating past crimes by running suspects’ photos against mugshot and driver’s license databases, as in the William case? Are they engaging in more dystopian practices, like using Clearview AI’s product? Are they tracking us wherever we go by hooking a facial surveillance capability up to real-time video surveillance feeds?

Second, without full information, defense attorneys can’t know whether errors in a facial recognition program or in how police used it led to a false arrest or other violation of their client’s rights. In the Williams case, police used a facial recognition algorithm called “Rank One.” According to a recent study by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, that algorithm — like many facial recognition algorithms on the market — has a worse rate of false matches when used on black men than white men.

As the ACLU and other organizations argued to the Florida Supreme Court last year, to mount a defense for their clients, defense attorneys are entitled to disclosure of full information about facial recognition systems’ error and bias rates, how the algorithms work, and how they are used. Otherwise, there’s a severe risk that police, prosecutors, and juries will let flawed technology make decisions for them, leading to dangerous injustices like what Williams experienced.

Third, even when facial surveillance technology produces a correct match, it raises acute privacy concerns, including possible violations of people’s rights under the Fourth Amendment or other federal and state laws. Criminal defendants have a right to challenge such violations in court, and to argue that evidence tainted by constitutional violations must be thrown out of the case. Facial surveillance technology places all of us under watch and infringes on our expectations of privacy, and we must push back against abuses in court.

Secrecy breeds abuse. And as we all learned from the rare look behind the curtain provided by the Williams case, there’s a whole lot of abuse.

While lawmakers work to halt law enforcement from using this technology, the government must at minimum meet its constitutional obligation to disclose when they are using this technology against us.

Nathan Freed Wessler, senior staff attorney, ACLU

For the opposite side of the argument read “Why we must arm police with facial recognition systems”