A new House bill would place enhanced restrictions on some financial institutions when it comes to paying ransomware groups.

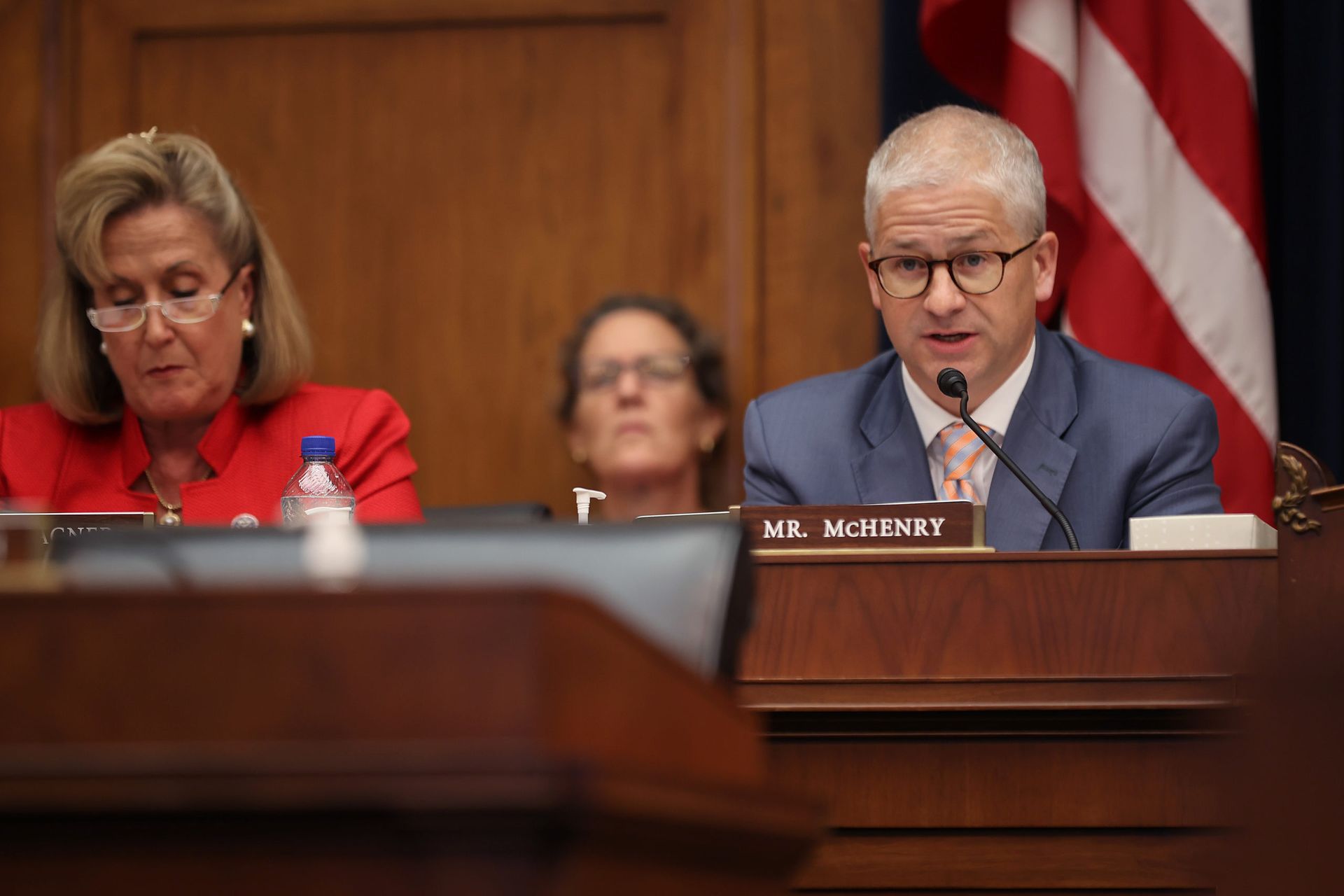

The legislation, introduced by Rep. Patrick McHenry, R-N.C., as an amendment to the upcoming consolidated funding bill by Congress, would require certain financial institutions to notify the federal government — specifically the director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network — and provide details about a ransomware attack before making a payment. It would also require special authorization to pay ransoms that are more than $100,000.

The bill would cover large security exchanges, financial market utilities designated as systemically important under the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, and technology service providers considered “significant” by the Financial Institutions Examination Council. The secretary of the Treasury would be responsible for developing formal guidance on the type of information that must be reported as well as rules for when and how special authorizations are dispensed.

McHenry, who serves as the ranking Republican on the House Financial Services Committee, cited the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attacks as an impetus for the bill’s creation, saying the long lines and gas shortages that resulted “pales in comparison to what would happen if America’s critical financial infrastructure were to be taken offline.”

“This bill will help deter, deny, and track down hackers who threaten the financial institutions that make day-to-day economic activity possible,” he said in a statement. “The legislation will also provide long overdue clarity for financial institutions that look to Congress for rules of the road as ransomware hacks intensify. I look forward to working with my colleagues and Treasury Secretary Yellen to protect our financial system from the 21st century threats they face.”

There are specific provisions in the bill that would protect companies from being held liable, criminally or civilly, solely based on the information reported and as long as the entity is making a “good faith effort” to determine the nature of the attack. It would also exempt the information from public disclosure in many cases.

Such protections speak to the delicate balance the federal government must uphold as it both encourages companies to report cyber attacks to the government — something that can help law enforcement collect vital evidence, scope out the impact of an attack and identify other potential victims — while still holding businesses and organizations accountable for neglecting their cybersecurity.

The Department of Justice, for example, houses both the FBI and the newly created Civil Cyber Fraud initiative, which will pursue hefty fines under The False Claims Act for government contractors that demonstrate cybersecurity malfeasance or deceit. While both missions have merit (observers say there are often few if any legal consequences when a company neglects its cybersecurity and suffers a breach) it creates a potentially awkward situation where businesses may be uncertain of how forthcoming they should be with the government and whether the information they turn over might eventually be used against them.

“The FBI has spent a lot of time … trying to convince victim companies that you can trust [them], you should cooperate fully and candidly to help us find the criminal and that the information you give us isn’t going to be used against you,” former Deputy Assistant Attorney General Kellen Dwyer told SC Media last month.