Over the past 18 months, we’ve tracked an ever-expanding and evolving family of fraud rings using fake mobile applications and communications over popular messaging platforms to lure victims into investment schemes, using emotional appeals, curated images and media, and well-scripted manipulations alongside well-developed mobile app infrastructure to gain the confidence of victims and walk them slowly into giving up their personal savings.

These scams, which we dubbed “CryptoRom” in our earlier research, became known in China as sha zhu pan (杀猪盘) (“pig butchering”). The scam form originated in China and went global during the COVID 19 pandemic—in part because of Chinese government crackdowns on cryptocurrency crime and other fraud within China, and in part because of expanding opportunities created by economic crises brought on by COVID.

In previous research, we’ve tracked how the perpetrators moved from targeting people in Chinese-speaking communities to an increasingly larger audience, and the extent of their technical resources. Recently, we discovered two scam rings had managed to publish applications onto the Apple iOS App Store, slipping past Apple’s rigorous review process. Pig butchering scammers are increasingly casting their net more widely, targeting victims in Western countries with the same tactics that they’ve used successfully throughout Asia.

As part of our continuing research into the criminal actors behind these schemes, I’ve continued to investigate the tactics, tools, and procedures common across them, and look for emerging trends. As an indication of how common they’ve become, I was approached by multiple, separate scam operations personally, each running different variations on pig butchering. I interacted with two of the scam operations in the hopes of extending our knowledge of them, as well as collecting the fake trading apps they used and data about their supporting infrastructure and organizational workflow.

The first, reviewed in this post, was a Hong Kong-based ring leveraging the MetaTrader 4 application—a legitimate trading application from a Russian software company that we have seen abused previously—to run a fake gold-trading marketplace. They used Windows, Android and iOS versions of the application, downloadable from a fake bank website; the iOS application used an enterprise mobile device management scheme to deploy to victims’ devices. To “enroll” in the marketplace, victims were instructed to upload a significant amount of personally identifying information, including photos of government identity documents and tax identification numbers, and then wire cash to the scammers.

The second scam (detailed in an upcoming report) was run by a Cambodia-based Chinese organized crime operation that ran a fake crypto trading application using the TradingView brand. The application, offered from a fake app store, came in Android and iOS “web clip” versions. This scam involved a much more developed social engineering operation, but followed the same pig butchering formula. Wallets associated with the scam app had visibly taken in about $500,000 US in cryptocurrency from victims in a one-month period.

We have shared data on these scams with Apple and Google, as well as other organizations that either were impersonated as part of the scams or were used as part of the swindle chain. We’ve also shared data with the companies used to provide infrastructure for the scams, and with appropriate CERT teams to aid in their takedown.

Both scams are still active. This is in part due to the difficulty of getting infrastructure operators to act to shut them down, and the “whack-a-mole“ nature of these operations—when one set of app certificates and infrastructure gets taken down, another springs up quickly to take its place.

You had me at “hallo”

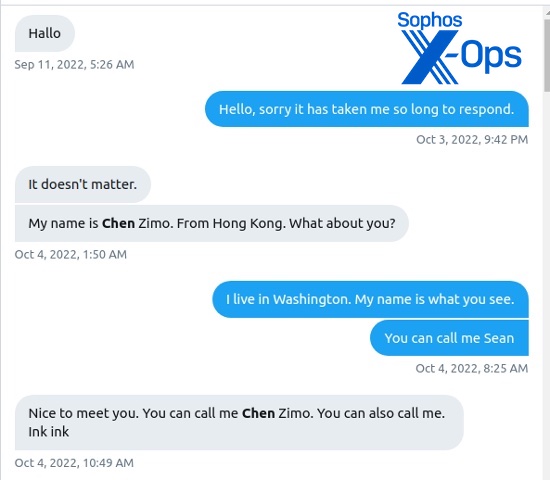

The first scammer I engaged approached me much in the same way as the liquidity mining scam we previously documented—via Twitter direct message. In fact, I left the DM untouched for nearly a month in my requests before engaging with it on October 3.

Starting with a “Hallo,” the scammer engaged me in Twitter direct messages to determine if I was a suitable target for the scam. “She” claimed to be a 40-year-old woman from Hong Kong. Shortly after I started responding, the account screen name was changed from “Alice” to “Chen Zimo.” This profile is still live on Twitter, though it was reported.

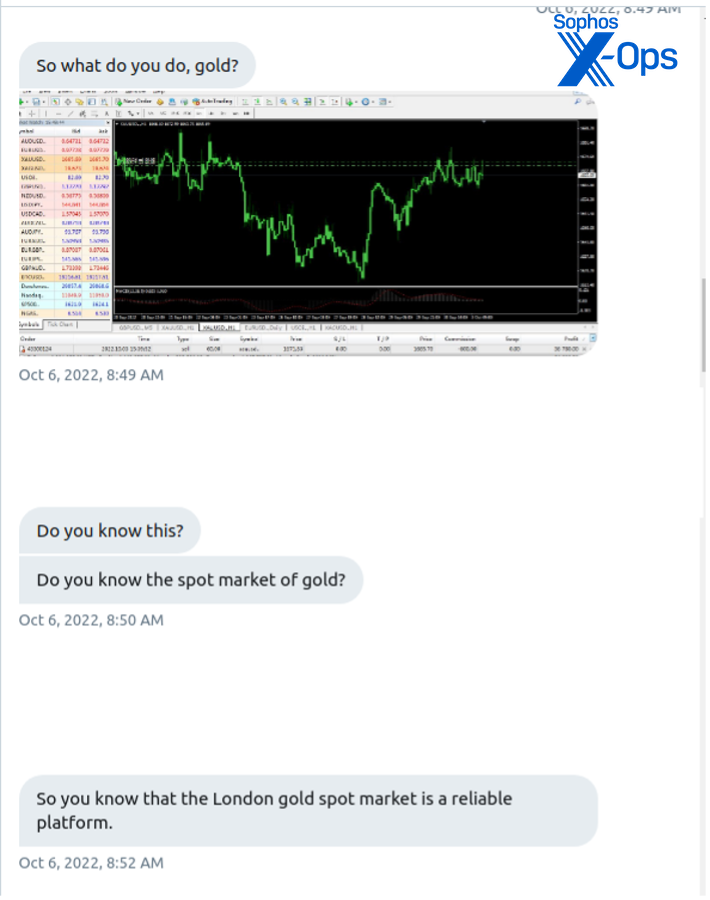

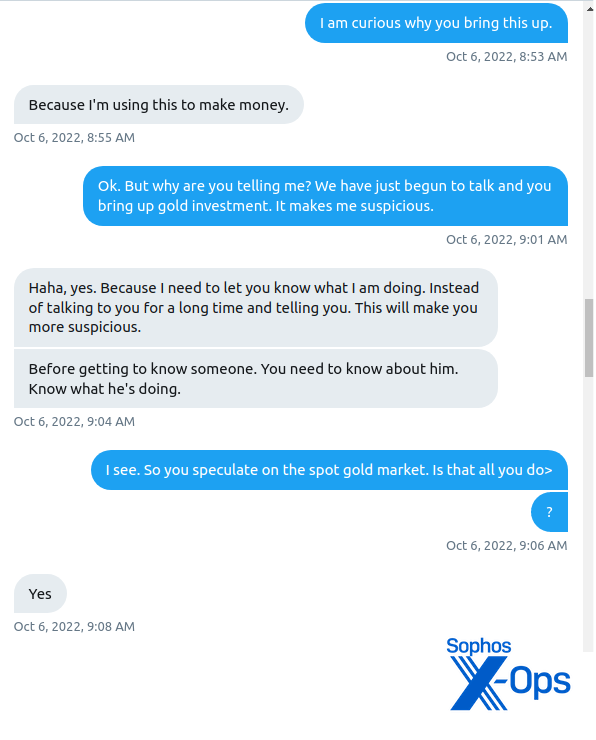

I told the scammer I was a cybersecurity threat researcher and that I investigated scams. “So you’re a cop?” the scammer asked. When I replied in the negative, the conversation quickly turned to investments—in this case, the gold market as shown below.

I expressed suspicion over the rapid movement in the conversation. The scammer tried to explain that this was an act of honesty, actually:

I let the conversation rest there for a few days.

When I picked up the message thread again, the scammer moved the conversation off Twitter, first asking if I used WhatsApp. I said that I didn’t, but I used Telegram. She said that was also good, and requested my account name.

Their Telegram account had a visible phone number listed with a UK mobile provider. A check of carrier information showed the number was with a carrier providing 3G legacy support and WiFi dialing—essentially making it a VoIP provider. After I added the Telegram account to my contacts, the scammer quickly changed their name (which had also been “Alice”) to “Chen Zimo” to match the Twitter account—but not before the first Telegram message.

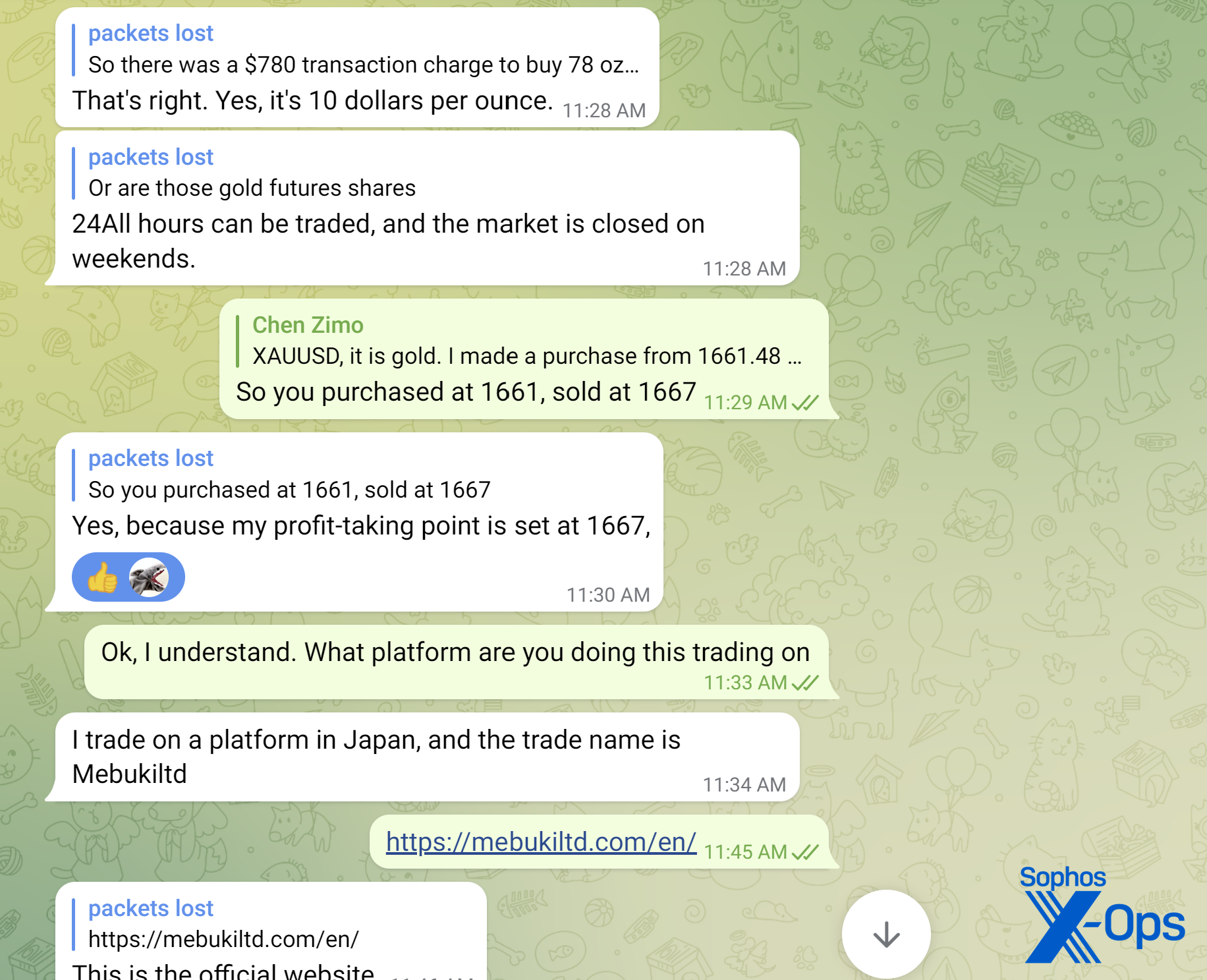

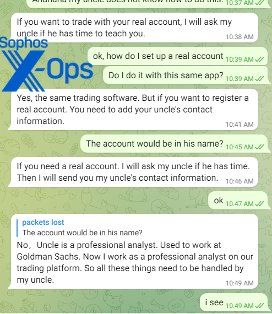

“Chen” told me that “her” uncle had taught her how to do short-term trading on the London spot gold market. While not taking an obvious hard-sell approach, pretty much everything the scammer messaged about was “gold trading”:

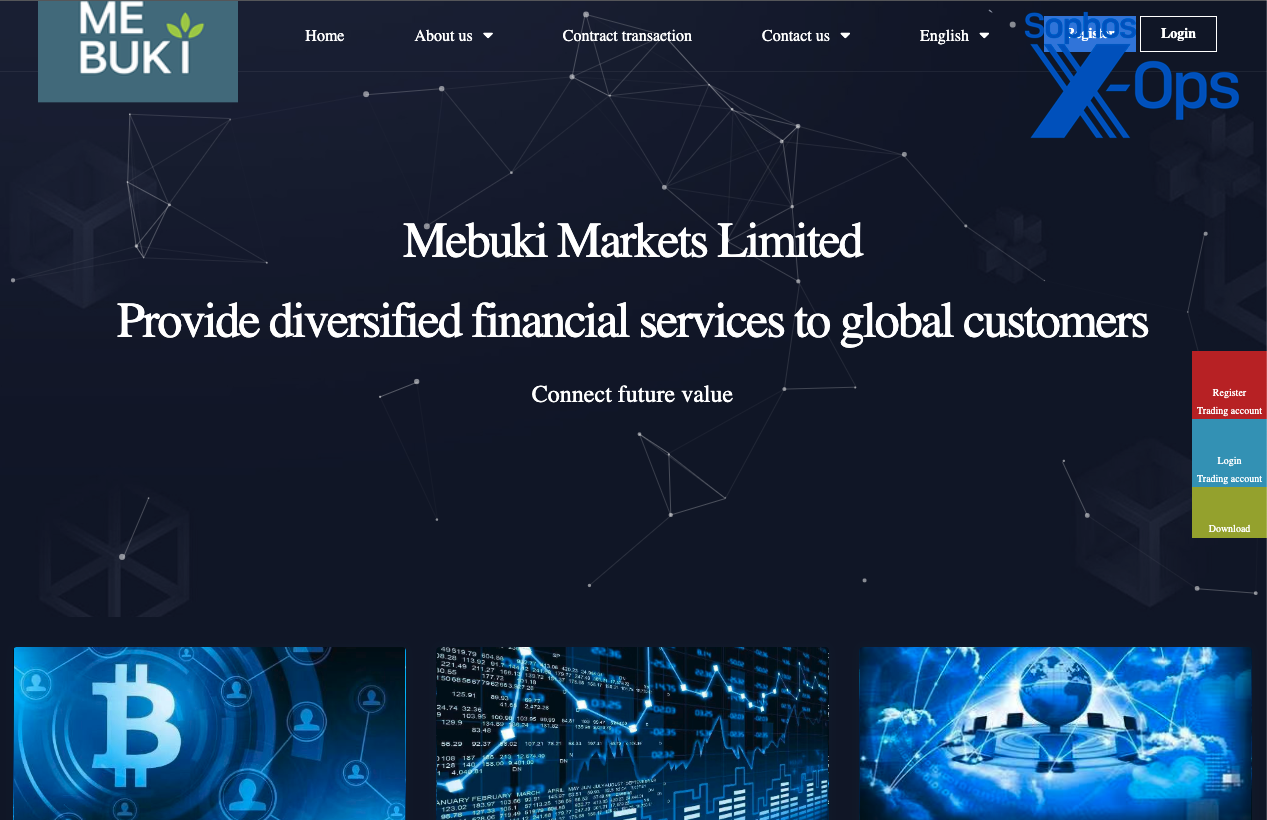

I asked some questions about the market platform she used. She provided a name, and I did a quick web search for it. Thanks to some good search engine optimization—including fake reviews posted on a foreign exchange tracking site– the fraud site appeared above the site of the legitimate company that the scam was impersonating–a Japanese banking company. The site appeared to provide foreign exchange and commodity trading services.

The scammer names the platform

The fictitious site, hosted in Hong Kong.

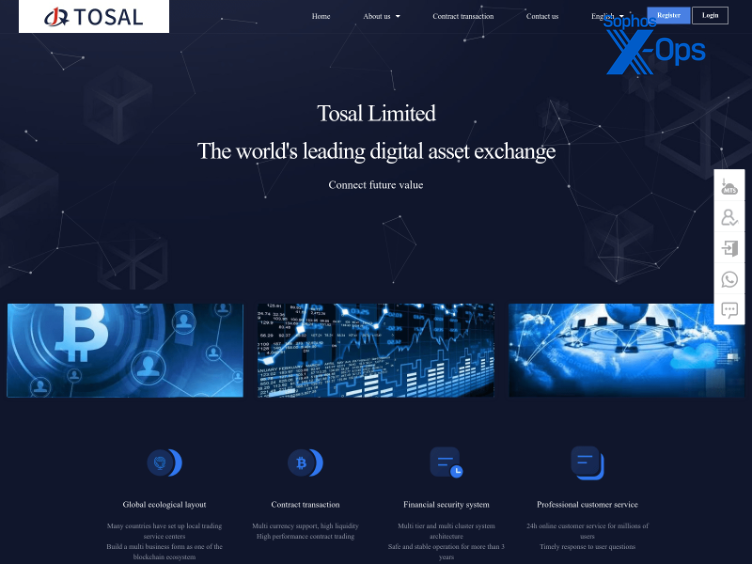

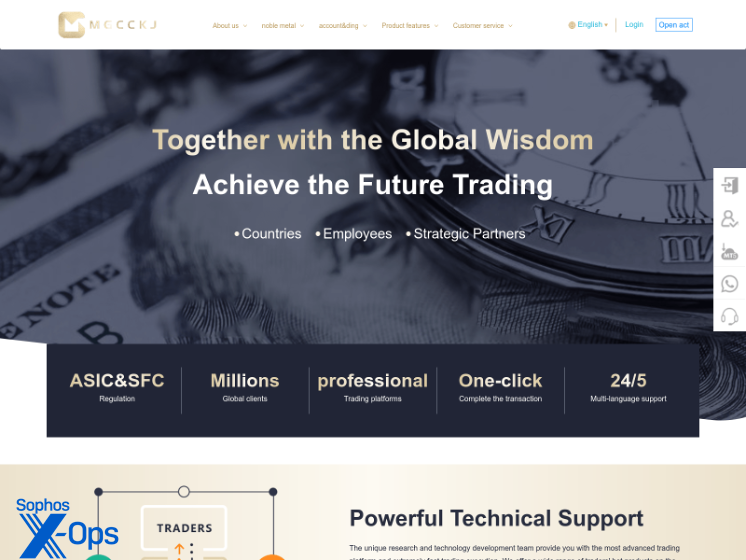

Researching the host used by the site uncovered nearly identical sites for several other brands, including one that used the same design as shown below. The server was hosted by Shenzhen Balian Network Technology Co. in Hong Kong. Further investigations turned up a total of 5 more sites running essentially the sam scam, but hijacking different brand names:

Again, I expressed some concern about the site, after collecting samples from the linked applications: “Why is the server hosted in Hong Kong? Why is this not hosted in the same place as the actual company’s website?”

At this point the scammer started complaining about me investigating all this. I had also found a reference to the site on a UK tax questions site, in which an “investor” inquired about having to pay taxes on earnings before withdrawing. This is a common tactic of pig butchering scams; to squeeze the final bit of cash out of victims, they often tell them through the fake app or website that they must pay as much as 20% of their fake earnings in taxes up-front before they can withdraw their money. They then cut off communications with the victim.

The scammer told me there was no taxes on this investment, that they were included in the trading fees and she had never paid taxes on the trades in Hong Kong.

One thing she was telling the truth about was her location. I had passed a tracking token via our chat, and confirmed she was on an iOS device in Hong Kong.

The scammer continued to engage with me, telling me about silver deals and other fictions. I then expressed interest in learning more about what “she” was doing—so I could start collecting further technical details.

Sanctioned apps

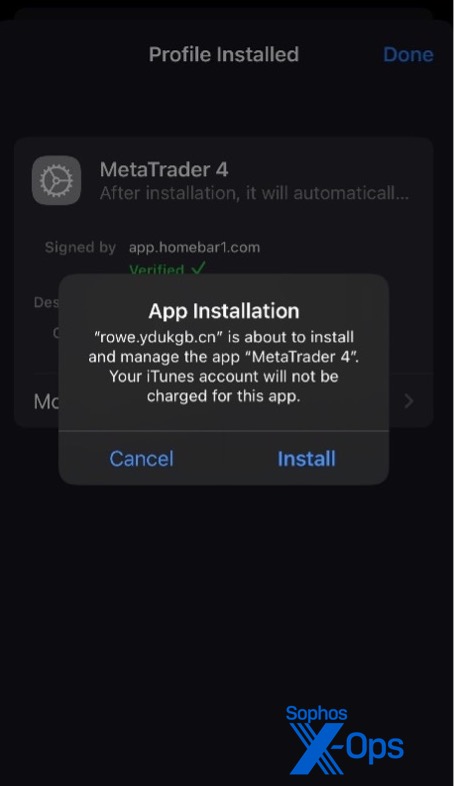

Surprised and happy about my sudden interest, “Chen” directed me to download the mobile app from the fake website and not the official Google Play, Apple App Store, or Microsoft Store. For Android and Windows, the fake apps are a simple download (of an APK and an installation .EXE, respectively). For iOS the fake app uses the 2021 .

The Windows app—a pirated version of the MetaTrader 4 desktop application–was already on our detection list. (A refreshed version was not, but we have since added it.) This application has a legitimate signature (though based on a Russian certificate), but its connection data has been altered to add a malicious server to its list. The same is true of the Android and iOS applications—on the surface both are legitimate apps, signed by the developer, but with altered connection metadata. Because of the query language used by MetaTrader 4, it is possible to essentially build new applications on top of the apps themselves.

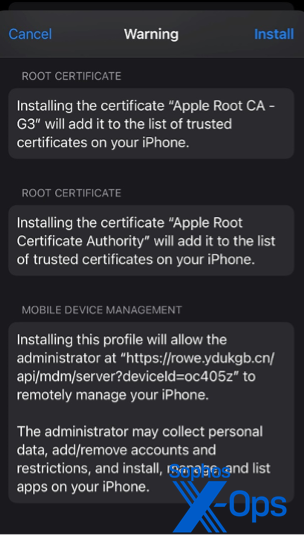

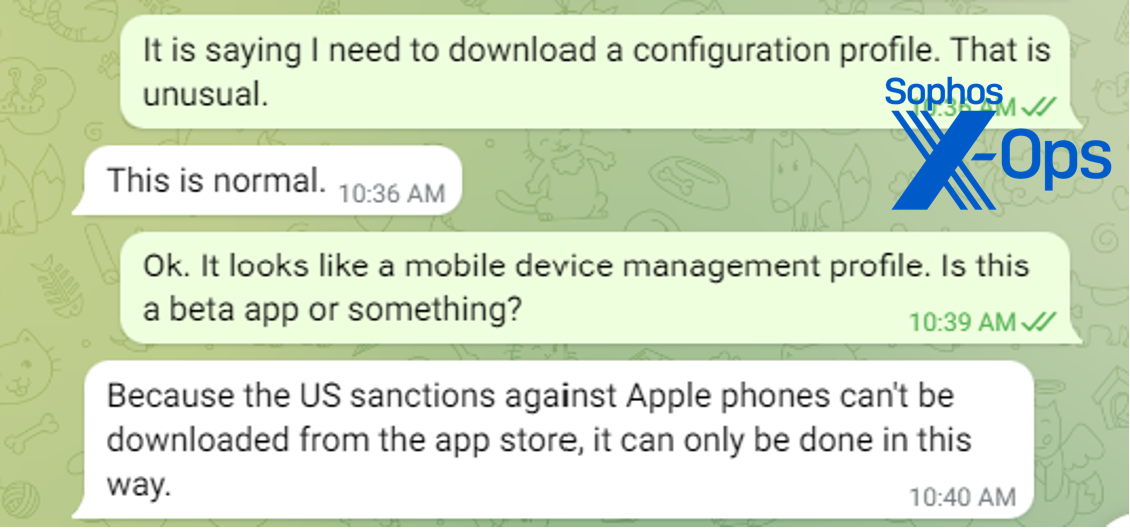

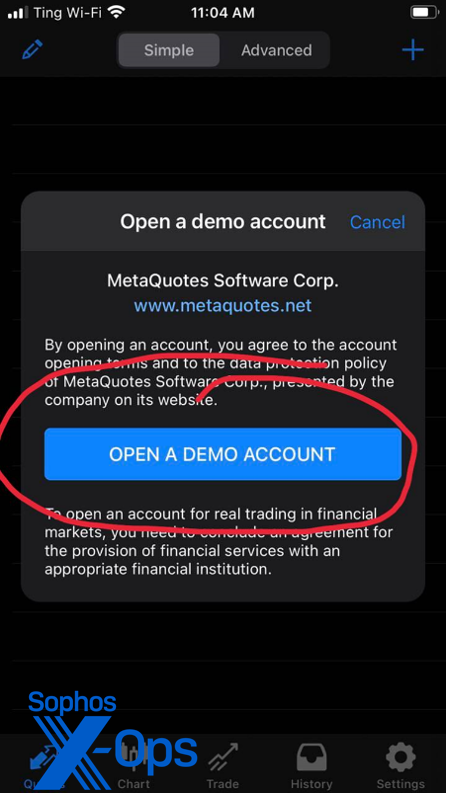

Both the Windows and Android apps were simple downloads. But for iOS, installation required accepting an enterprise mobile management profile connecting my (test) phone to a server in China – a huge red flag, but one that many users could be socially engineered to ignore.

I asked why I had to download the app this way and was told it was “US sanctions”:

In fact, that’s semi-accurate—MetaTrader 4 is developed by a Russian software company and is not available in the US Apple App Store. The version downloaded off the fake website is only slightly modified, to include a list of backend servers that points to the one controlled by the scammers. The fact that the legitimate app is not available on the iOS app store is a boon to the scammers, as there’s no way for the target to simply download a legitimate copy.

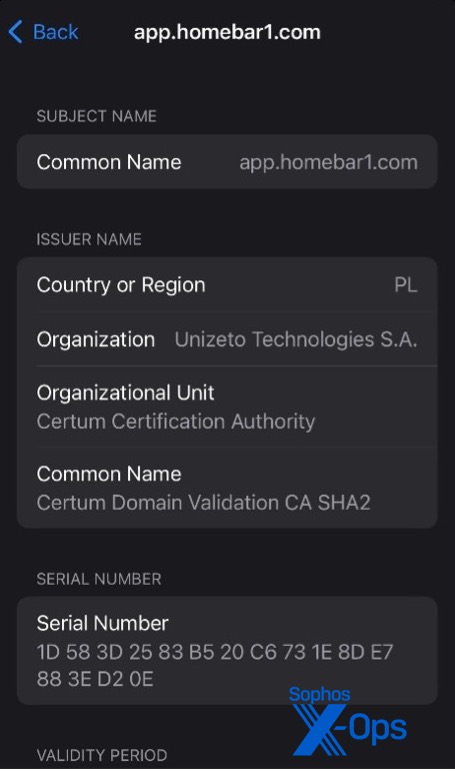

Before going forward with the iOS app download, I began a packet capture of the traffic. The full list of domains and IP addresses involved in the criminal application infrastructure is provided in the IoC file linked at the end of this report. Most of the elements were hosted on Binfang and Alibaba hosts, with some content provided through Cloudflare; some certificates were staged using Akamai.

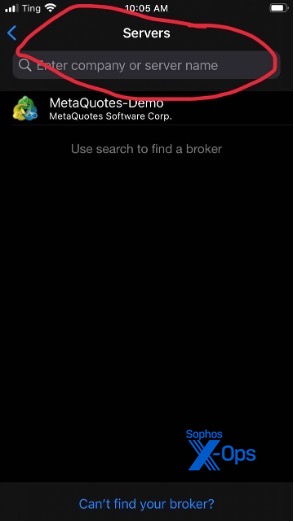

I was walked through the installation by the scammers, who sent screen shots with red circles to show me where to tap. I was guided through finding the right server name in the configuration (one that mimicked the financial institution the scammers were imitating):

Connecting to MetaQuotes’ server fails because of the altered configuration…

So the scammer directs me to type in the fake bank’s name…

When I tapped the right one, I was then guided through setting up a “practice” account with a balance of $100,000. Once that was complete, the app displayed a market tracking screen—one streamed live from another server in Hong Kong.

After a few lessons in how to set up trades, profit-taking points, and loss limits—each of which the scammer guided me through with screenshots matching the time of our discussion– the scammer offered to introduce me to her “uncle” to guide me through setting up a real account and getting trading tips.

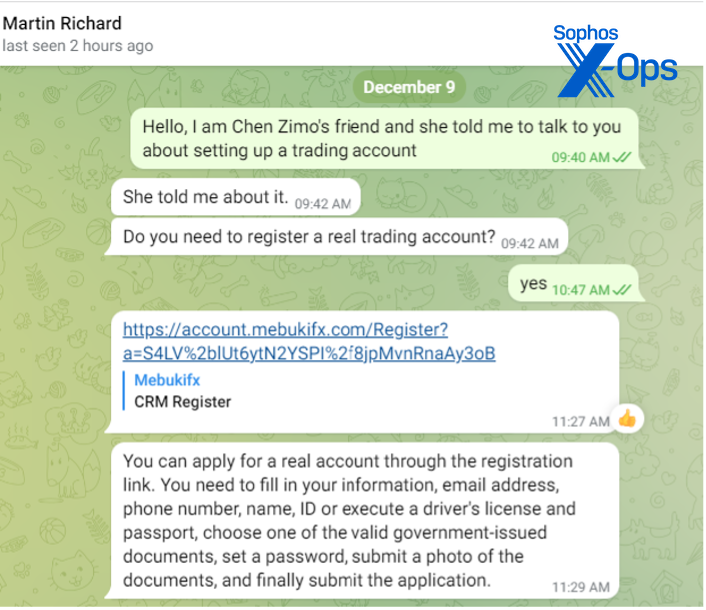

“Uncle Martin Richard” had quite the (fictional) pedigree—the scammer claimed “he” was a former Goldman Sachs analyst.

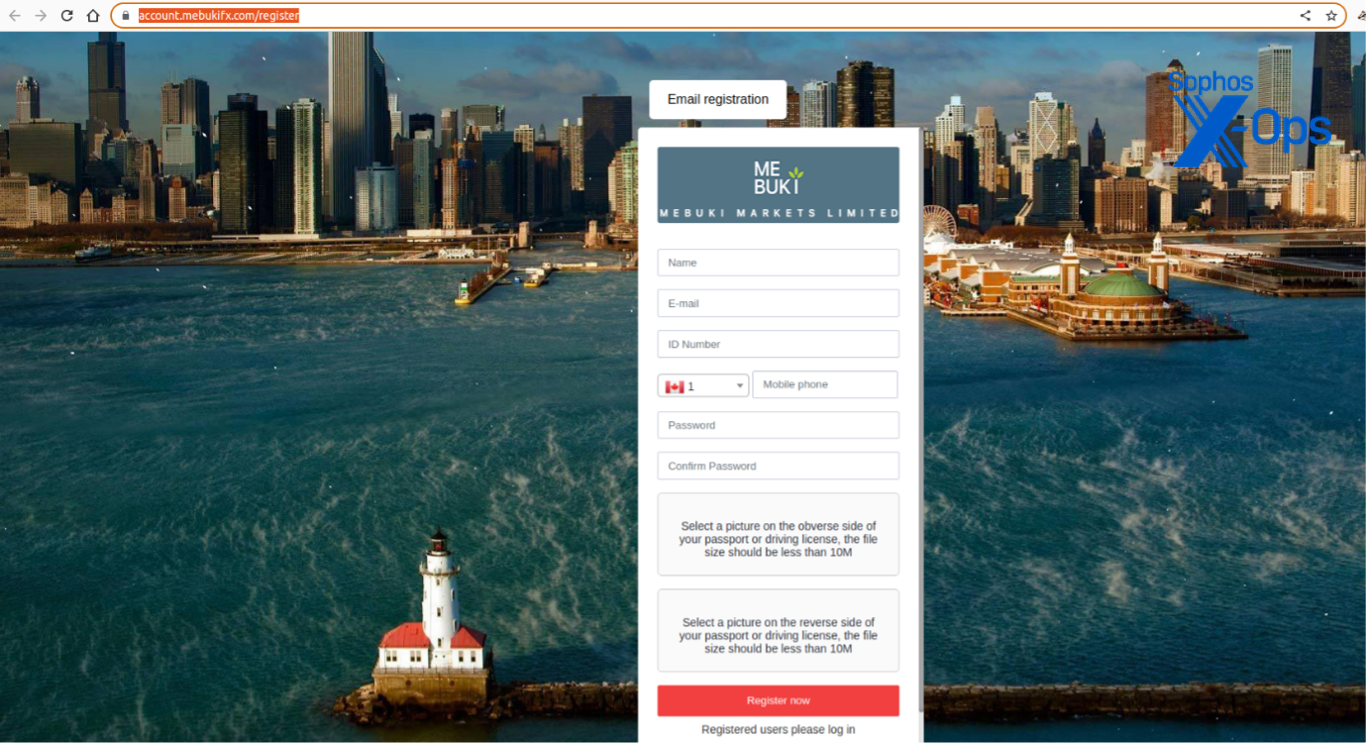

“Martin Richard” told me to register an account through yet another scam host page. It mimicked a Know-Your-Customer style registration, requesting photos of government ID. The site also had animated snow in the background, and a picture of downtown Chicago (recognizable by the Navy Pier and a few other landmarks):

Once a “real” account was set up, “Martin” said, I would be able to deposit money and start executing trades at his direction.

The “Martin” Telegram account, unlike the “Chen” account, used a US number registered through Peerless Network, another VoiP provider.

Whacking the Mole

Work on the scam began in October, and much of the initial gathering of technical details happened in November. We shared information on this actor with Japan CERT (because of the brand jacking involving a Japanese financial institution), Apple, Google, and others. We reported the initial enterprise app distribution “team” to Apple, and labeled the domains as malware hosts in our reputation database.

But as these actions took hold, the scam operation shifted to new domains. I told the scammers I no longer was able to get the app downloaded to work, and they dutifully pointed me to the new download infrastructure (using the domain mebukifx[.]com) and new enterprise mobile provisioning profile.

As Jagadeesh Chandraiah reported in earlier examinations of these schemes, the abuse of the iOS enterprise application distribution scheme appears to be done through a third-party service for iOS developers. Ad hoc application distribution is not exceptionally unusual in much of the world because of the limitations of the official Apple Store, particularly those put in place to meet with Chinese government mandates. When the developer licenses associated with one of these services is pulled, the service providers simply stand up another one, or their developers move to a new distributor.

Grading the scammers

This particular scam operation was not as polished as some of the others I’ve dealt with from a social engineering standpoint. The efforts to engender a relationship were limited to a few photos and a video sent to establish the false identity. At one point the “uncle” began responding in Chinese to questions in English. But the technical sophistication of the websites and the mobile apps may have been enough to convince some victims to transfer cash into their fake exchange, and engagement in other languages may have been more convincing.

In comparison, the next case I’ll be discussing—a Cambodia-based ring running multiple crypto trading scams—had a much more developed backstory with more direct engagement. The scammers used a combination of flirtation, matching of interests, and voice and video calls over the messaging app to bolster trust-building. (For example, when the scammers learned I had a cat, their spokesperson suddenly also had a cat.) While the Hong Kong-based ring had low-intensity engagement because of the time difference, the Cambodia-based scammers worked on North America time and messaged multiple times per day.

Because of the fluid nature of the technical side of these scams, the only reliable defense against them is public awareness of how these threats operate. What may have been obvious as a scam to me may not have been picked up upon by many educated people in vulnerable situations—which, given how the COVID 19 pandemic and its aftermath have affected many people, is a substantial population of potential victims. And these scams will only grow more sophisticated with time. This scam’s focus on gold—something many people will have greater confidence in than cryptocurrency—is an example of how these scams will continue to find niches that they can exploit.

Indicators of compromise for this scam can be found on the SophosLabs Github page here.