A coding slip up made by social media site Parler offers practical lessons to the broader security community about the reputation fallout and even legal and competitive ramifications that can come with a failure in security protocols.

This week, users of Parler learned researcher had archived nearly all the posts to the social media site preferred by the extreme-right in the haze of the D.C. insurrection — including many of those that users thought they had deleted.

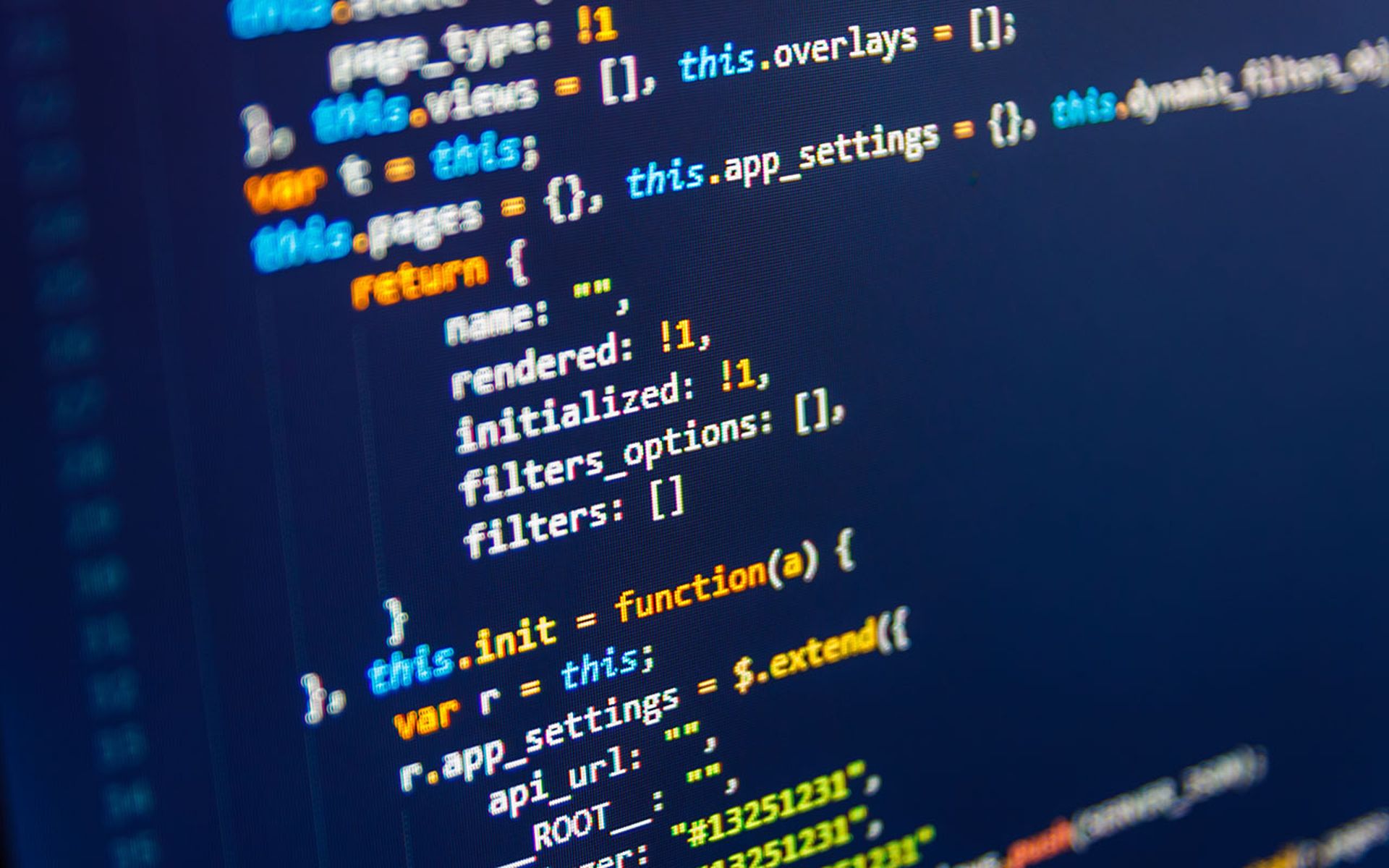

The researcher, who goes by @donk_enby on Twitter, took advantage of insecure direct object references (IDOR), a failure to secure unique parts of the site. In Parler's case, it played out like this: each post was given a numeric identifier. Anyone using the site's API could access a post by giving the number with no other authenticator. So, anyone who wanted to access every post ever put on the site could do so by requesting post one, then two, and so on into infinity.

Parler did not thoroughly remove deleted posts according to @donk_enby. Requesting them by number would allow anyone access. Applied to internet applications in general, IDOR problems could extend to anything stored sequentially and not secured individually — receipts, posts, and in many instances entire accounts.

"IDOR is a really easy mistake to make," said Casey Ellis, founder and chief technology officer of bug bounty and disclosure platform Bugcrowd. "IDOR is everywhere."

Ellis said that the error is most common in high growth websites prioritizing expansion over secure coding practices, or in websites based around legacy code. Given time to consider their work, most modern programmers are at least familiar with the issue and able to identify workarounds.

"There are layers to Parler's IDOR problem — they shouldn't have done IDOR because it isn't secure, but should have been even more cautious because of what was at risk by not protecting data," said Ellis.

Parler advertised itself as a free speech platform, standing up for the right-wing content that would often be moderated away in other platforms — including physical threats and debunked conspiracy theories that undermine elections or public safety. Yet leaving deleted posts open to IDOR introduced risk for users of the conservative response to liberal safe spaces.

In short, said Ellis, an event like the Capitol insurrection, where someone would want to download evidence in bulk, should have been foreseeable and within the threat model for defense.

“Cybersecurity and information warfare used to be separate issues. We’re in the middle of cybersecurity and information warfare converging,” said Ellis.

In the broader sense, organizations should worry about scraping for a bevy of reasons. The theft of price data, for example, can be used to gain a competitive edge in the marketplace.

Protecting against IDOR isn’t the only defense companies should put in place, said Shuman Ghosemajumder, Global Head of artificial intelligence at F5 Networks.

“Large platforms have at least some mechanisms in place to prevent someone from scraping huge amounts of content at high speed. The simplest example of such a mechanism is an IP rate limit, where you only allow a single IP address to access a certain number of posts per second, thereby limiting the ability to scrape huge amounts of content using a bot,” he said, via email.

Rate limits, noted Ghosemajumder, are only a defense against unsophisticated actors. More sophisticated tools are needed against more advanced bots.

Legal protections against scraping, from IDOR or otherwise, remain unsettled. The Supreme Court just heard oral arguments in a case to determine whether violation of a site’s terms of service equates to violation of the law under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the country’s main hacking statute.

At issue is the meaning of "exceeds authorized access" in the CFAA, said Mark Srere, co-leader of the investigations, financial regulation, and white-collar practice group at the law firm Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner.

If violating a site’s terms of service exceeds authorized access for a website, a scraper is open to both civil and criminal penalties. But courts so far have been split about how broadly to interpret the law. The case before the Supreme Court, for example, directly concerns whether a police officer convicted of illicitly using a police database violated the CFAA by accessing information he would have legal access to for official use.

There are reasons that violating terms of service is still a controversial application of the CFAA. Most people believe there is at least some degree of benign lying on the internet that shouldn’t be prosecuted by law.

“What if you lied about your height and weight on Tinder?” asked Srere.

Regardless of the outcome of the case, he added, most businesses will want more advanced protections against scraping than the courts are in any position provide.

“I would suspect there is a technical solution better to rely on than a legal" one.