Water is wet. The sky is blue. And sometimes, people who make grandiose claims aren't being entirely honest.

In April, several news outlets reported LinkedIn had suffered a massive breach based on a hacker claiming to have 500 million private records of users. But the hacker appears never to have actually breached LinkedIn, instead scraping together a large file of publically available data from the site. Earlier this month, the Republican National Convention profusely denied being breached after a media report, claiming instead that one of its contractors had been breached in a way that did not expose the political party. Just last week, Saudi Aramco denied that stolen internal documents being hawked by a hacker were stolen from the firm. Instead, the oil giant said, they had been stolen from a contractor.

If your first response to hearing a company deny being hacked is to think "They're probably lying" or "They're probably unaware of what happened," that is because enterprises have a bad track record of getting a breach wrong before they get it right - having to revise the scope of data accessed, numbers or even if a breach happened at all.

But what if a company is confident claims are wrong? In many cases, say experts, there may be no good way to promptly convince the public a breach is bunk.

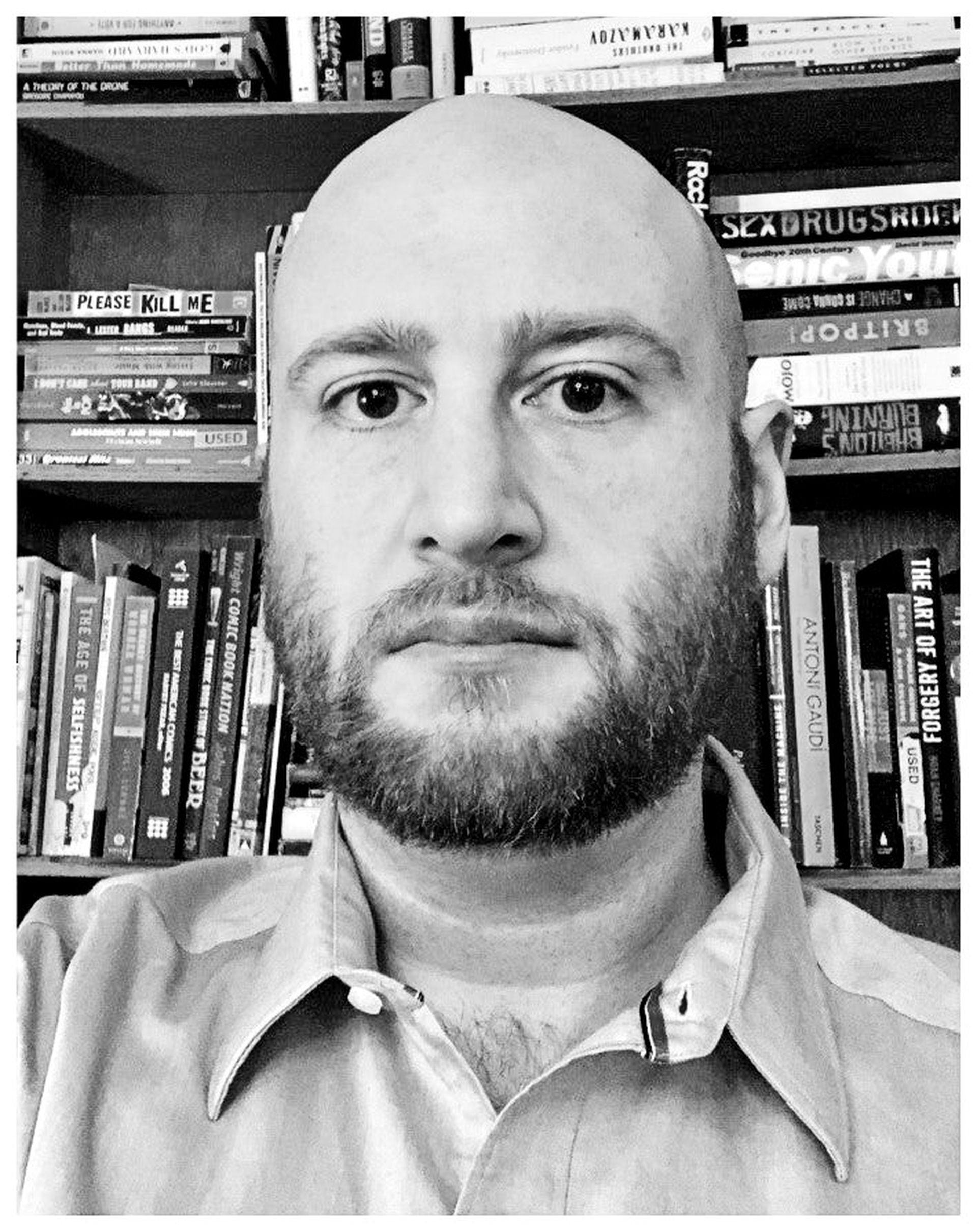

"The No. 1 thing we always do is find the truth, find what the true story is," said Josh Zecher, co-founder and partner of strategic communications firm Vrge Strategies. "I'm of the belief you can't PR your way out of something; you have to have facts behind it. But due to the complexity of investigating a breach, it could take three to four weeks to identify the entire story."

In that time, the attention that was focused on one maybe-breached firm may have long moved on to any other maybe-breached firms. Or a political scandal. Or a dog who cooks pizza. The unsatisfying answer for many victims of stories might be that they don't get a chance to defend themselves while the iron is hottest.

Rumors can make companies feel desperate to respond quickly, even when a dispassionate third party would recognize there was no reason to respond.

"I feel like our job as an outside consultant, is it's not as personal to us necessarily, and it's our job to really measure the risk and the reward of refuting something rather than making it more public," said Zecher. "If the rumor is on Twitter and the person has 150 followers and we don't see it being picked up anywhere, why amplify that? But our job is also to be prepared in case it does get amplified."

Responding too quickly is not only a communications problem, but can also become a regulatory one.

"If you're stating, 'We weren't compromised, those aren't our documents' and then it turns out that those are your documents, and you have been compromised, that doesn't look good to a regulator," said Christian Auty, a partner with the law firm Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner.

Auty said that caution was key. He has seen cases where enterprises were 100 percent sure they had not been breached find that a contractor was breached, and leaked files were authentic.

That does not mean staying silent if you can definitively prove a leaked password list wasn't yours. "By all means, defend yourself if they are pointing to something specific and you can credibly prove 'No, it's not me,' " he said.

But, he warned, be prepared for investigations to take time. Establishing that something did not happen is difficult.

"Proving a negative is always impossible," said Jake Williams, co-founder and CTO of BreachQuest, "but increasingly it’s what organizations are challenged with. Sometimes an organization really hasn’t been breached."

He said oftentimes, when enterprises have been breached but were sure they had not been, it is because data is in an overlooked place, like marketing databases or weakly defended SaaS applications.

The best way to convince the public that a breach did not occur, said Williams, is to be able to transparently show a thorough investigation.

"Saying 'We have no evidence of a data breach' doesn’t tell an educated reader anything about what you’ve done to come to that conclusion," he said.

Even then, convincing the public of the truth can be difficult. Several publicity firms contacted for this story said it was important to establish an enterprise's reputation for honesty before that honesty would first come into question.